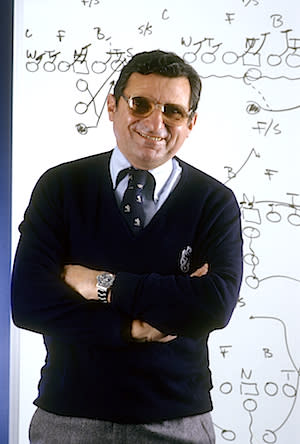

RIP Joe Paterno

A little more than two months after being fired from the job he made his life, Joe Paterno is dead.

The family of the iconic coach, owner of more wins than any other coach in the history of college football, issued a statement confirming Paterno's death this morning, a little more than a week after he was admitted to a local hospital with complications from lung cancer. His family had reportedly been summoned to the hospital Saturday evening. He was 85 years old.

[ Related: Dan Wetzel: Joe Paterno's legacy damaged by scandal, but not erased ]

And now the really hard part. As impossible as it is to overstate the impact of Paterno's 62-year tenure at Penn State, it is equally impossible to ignore the tragedy of his final months. There is really no other word: Once a universally beloved titan of American sport, he ended his life as a frail, sick man, cast out by the institution to which he'd devoted that life — his life and his career being virtually inseparable — his formidable legacy stained by a scandal that will likely follow his name as long as anyone remembers it.

His death comes with two levels of grief: One for the man as a husband, father and mentor to thousands of players, students and coaches, and one for the man as an icon, who lived just long enough to see the program he built under the creed "Success With Honor" crumble around him. This close to the grief, it may also be impossible to resolve the cognitive dissonance between such contrasting portraits of the same man. There are still too many open wounds and unresolved threads to predict how or when that legacy may be pieced together and held up as a beacon again, if it ever will be.

There is a vast chasm separating his disciples and his critics, with their dueling visions of the professor who succeeded at the highest level for decades with unsurpassed integrity — the embodiment of "doing it the right way" — and the magnate who fostered a culture so insular and self-reverential that even charges of a heinous crime were subordinated to "the family." The bridge between the two sides has not even begun to be built.

It is a sad fact that any celebration of the greatness of Paterno's career must also wrestle with its ignominious end. As far as the sequence of events that brought his administration down is concerned, Paterno made a pretty compelling case against himself. According to his grand jury testimony, he was informed in 2002 that "inappropriate action was taken by Jerry Sandusky with a youngster" in a Penn State shower. He knew that said action was "of a sexual nature." Sandusky had been investigated on virtually identical charges by university police once before, in 1998 (the department produced a 95-page report on the investigation), and was later investigated again by his charity, The Second Mile, in 2008.

Still, Sandusky maintained an office in the Lasch Football Building and (according to the Pennsylvania Attorney General) had "unlimited access to all football facilities" for the better part of a decade, including the locker room. He also kept a parking pass, a university Internet account and a listing in the faculty directory. As recently as 2009, he was still running an overnight football camp for children as young as 9 on a Penn State campus. He was still working out in football facilities as recently as last October — months after university officials (including Paterno) had been called to testify in the investigation that ultimately led to his arrest on more than 40 counts of sexual abuse against at least eight victims over more than a decade. Sandusky told the New York Times in December, more than a month after his arrest, that he still had his keys.

It's still up to a jury to determine whether there's enough evidence to convict Sandusky of committing the heinous acts he's accused of committing, and another jury to determine whether Paterno's former bosses, athletic director Tim Curley and vice president Gary Schultz, fulfilled their legal obligations when informed of the accusations. According to prosecutors, Paterno fulfilled his.

But there is no way around the fact that Penn State officials — Paterno among them — continued to accommodate and to some extent shelter an alleged sex offender for years despite multiple, credible accusers. Presented with allegations of serious criminal behavior in his program, in his locker room, Paterno merely ran it up the chain. Then, when nothing happened, he looked the other way. He didn't inform the police. He didn't disassociate with Sandusky. He didn't move to keep Sandusky off campus. He didn't move to keep Sandusky from working with children on a regular basis.

[ Related: Coaching timeline of Joe Paterno's Penn State tenure ]

He ran it up the chain, and he let it go. If officials at a high school where Sandusky volunteered hadn't taken action, he would still be there, enjoying "emeritus" status and the tacit acceptance of an institution that had consistently declined to see what it didn't want to see. The admonition is true: Joe Paterno was not a victim. He was not a scapegoat.

Lack of due diligence notwithstanding, he also was not a fraud. By any measure, it's equally true that Paterno belongs among the pantheon of the most accomplished and progressive coaches of the 20th Century. He's an original: Sincere about his commitment to education, ahead of the curve on race, unfailingly loyal (to a fault, as it turns out), and massively successful on top of it. The scandal that ended his career doesn't affect his status as the winningest coach in the history of the sport. The record win total is still there. Six undefeated seasons, two national championships, three Big Ten titles. The philanthropy is still there. The $4 million donated back to the university, evidenced in the library that he helped build. The hundreds of players who are still willing to stand up for him based on "the immense quality of Joe's character." For them, there is no Penn State without the values that JoePa instilled, and they literally cannot imagine a Penn State that doesn't explicitly embrace the same values.

The reverence for Paterno was never a matter of mere longevity. Nor was it invented out of thin air: He was the mentor, teacher and winner he has always been purported to be. Some measure of the debt that college sports owes to the man and the deep respect his career deserves will survive in hallowed, Wooden-esque tones, and it will all be true.

And so we're left with the contradiction of a fundamentally decent man whose career and values can never be completely separated from his most egregious lapse in judgment. To argue that Paterno had no responsibility beyond his legal obligation in the Sandusky scandal is to reduce him to a buck-passing middle manager in a program and university that he defined. To claim we don't have enough information about his response is to ignore the implications of Paterno's own account, along with everyone else's. To protest his exit as head coach is to deny all ethical, legal and political reality. And to deny the tragedy of a 62-year career crumbling around a man who has meant so much to so many people is to deny that his life's work had any meaning.

It did, and it does. His family, his players and his university are a testament to that. Fleeting as wins and losses may be, so does his record. For as long as a I can remember, since devouring books both by and about Paterno as a teenager, I've considered him the greatest living coach in football — maybe in any sport — because he achieved what he set out to achieve on all of those fronts: Success With Honor. Now, he is no longer living, and the honor that defined the second half of his life has been significantly tarnished. His "Grand Experiment" to integrate a championship football team within the academic mission of a leading research university lives uneasily alongside the specter of a predator finding a haven in his locker room.

It is not "heads" or "tails": Both sides of the coin are equally, tragically true. They are both part of what Paterno built, and what he leaves behind. In time, it may be that his staggering success finally shines through the fog that descended on the end of his life. But now that the obituaries are being written, assessing the man and his legacy on his last day on earth means coming to grips with both, with all that implies.

- - -

Matt Hinton is on Facebook and Twitter: Follow him @DrSaturday.

Other popular content on Yahoo! Sports:

• Former President Clinton bringing his charm to PGA event

• NBA mascot breaks backboard on dunk, forces game to move

• Clint Dempsey scores first American hat trick in Premier League