Biden's White House is pushing to undo the crack cocaine sentencing disparity. But will enough Republicans support it?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Corrections & Clarifications: An earlier version of this story misstated the Republican support for the proposal in the Senate. Two Republicans, Sens. Rand Paul, R-Ky., and Rob Portman, R-Ohio. have co-sponsored the bill.

WASHINGTON – The year was 1986, and fears over crack cocaine were at a fever pitch.

New York City, as one headline put it, was "swamped by 'crack.'" Faced with a media frenzy and a high-stakes election year, Congress hastily passed a law that punished crack cocaine offenses far more severely than powder cocaine offenses – a policy that sent a disproportionate number of low-level drug offenders, most of whom were Black, to prison.

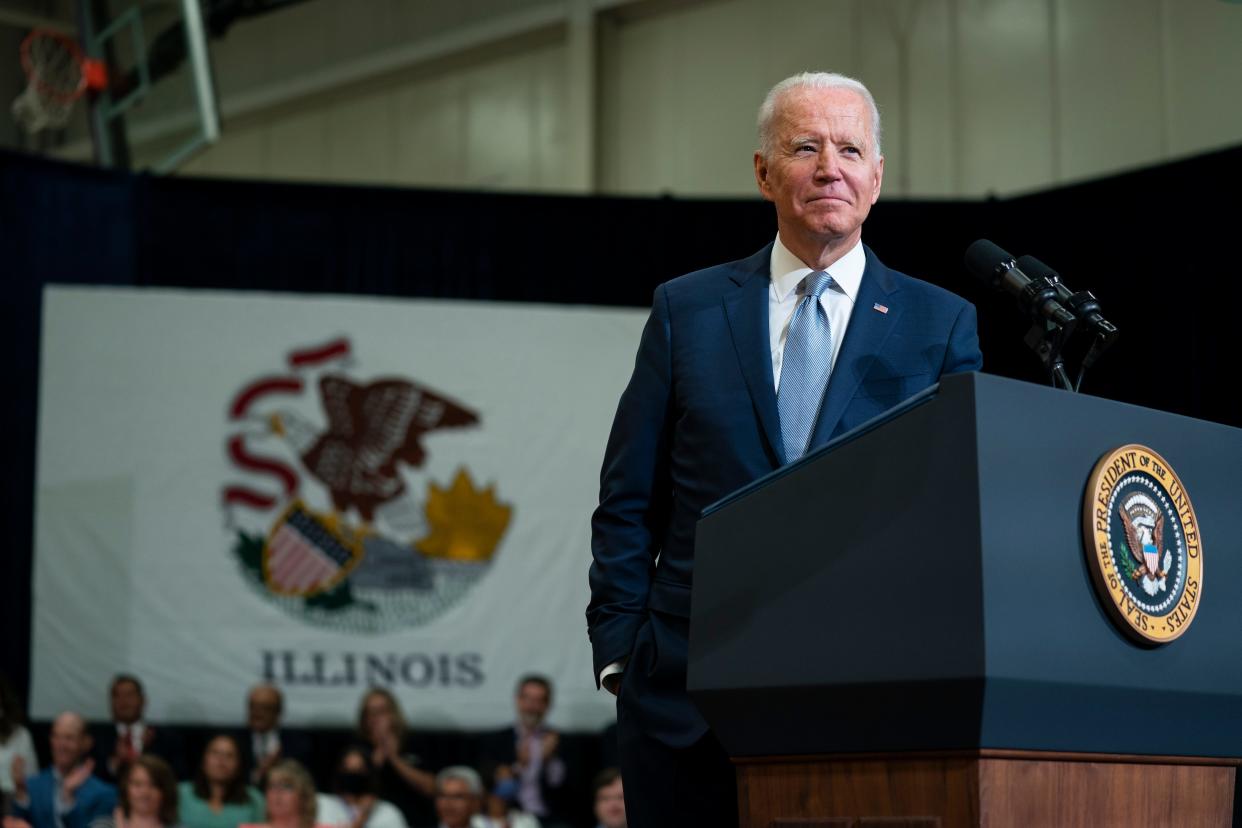

Thirty-five years later, lawmakers are trying to undo the consequences of what they now believe is a misguided law, a brutal consequence of the war on drugs. President Joe Biden, who helped craft the 1986 bill when he was a senator and has since tried to undo its impact, has placed his White House behind new legislation that would close the disparity by allowing crack cocaine offenders to ask for a reduced sentence.

Advocates say a nationwide reckoning over race following the death of George Floyd has created the right political environment to reverse a fundamentally racist law. But some say political rhetoric over rising violent crime may keep conservatives from backing legislation that essentially helps criminals.

'America First': Vowing loyalty to Trump, 'America First' groups try to bring nativism into the mainstream

Eric Sterling, a former House Judiciary Committee counsel who helped draft the 1986 bill and who has since worked to undo its consequences, is doubtful that Biden's backing is enough to sway enough conservatives to support the bill known as the EQUAL Act.

"The president's support does not provide political cover for Republican members of Congress or senators. No Republican is going to be campaigning and saying, 'I was with President Biden on low-level drug offenders.' The sound bites don't work," said Sterling, former executive director of the Criminal Justice Policy Foundation.

'A no-brainer'

Under the 1986 bill, a person who sold 5 grams of crack cocaine received the same punishment as someone who sold 500 grams of powder cocaine. The 100:1 disparity meant that street-level retailers were punished more severely than wholesale drug dealers, according to the nonpartisan U.S. Sentencing Commission.

The Sentencing Commission has repeatedly urged Congress to close the disparity after finding that the severe punishment exaggerated concerns over violence and abuse tied to crack cocaine. Congress acted in 2010 – 25 years later – by reducing the ratio to 18:1.

But recent data from the commission showed that Black prisoners still represent a disproportionate number of crack cocaine convictions. Nearly 90% of federal prisoners serving time for cocaine trafficking are Black.

The Justice Department said "it is long past time to end the disparity," according to written testimony endorsing the EQUAL Act, which would bring the ratio to 1:1.

Biden: Joe Biden wants to provide millions of Americans with high-speed internet. It won’t be easy.

"In our view, this should become a no-brainer," said Kevin Ring, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums. "This is something that is a stain. It's something that has been offensive to Black Americans for decades."

But Steven Wasserman, vice president of policy for the National Association of Assistant U.S. Attorneys, told the Senate Judiciary Committee last month that the bill would overburden understaffed federal prosecutor's offices, which will have to review cases. Wasserman also disputed that crack and powder cocaine should be treated equally, saying that while the drugs are chemically the same, the method of ingestion – smoking – makes the high more short-lived and more intense. He added that crack cocaine offenders have more extensive criminal histories.

Wasserman urged lawmakers to consider making punishments for powder cocaine offenders more severe to match punishments for crack offenses. Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., proposed a separate bill that would do just that, but proponents of the EQUAL Act say doing so would only send more low-level offenders to prison.

"That's exactly backwards," Ring said.

Republican support is key but some say unlikely

Sixteen Democrats and 16 Republicans have signed on to support the bill in the House.

"This discriminatory sentencing has been an ongoing issue for a long time," said Rep. Don Bacon, a Republican from Nebraska who was one of the early co-sponsors. "We must eliminate the crack and powder cocaine sentencing disparity."

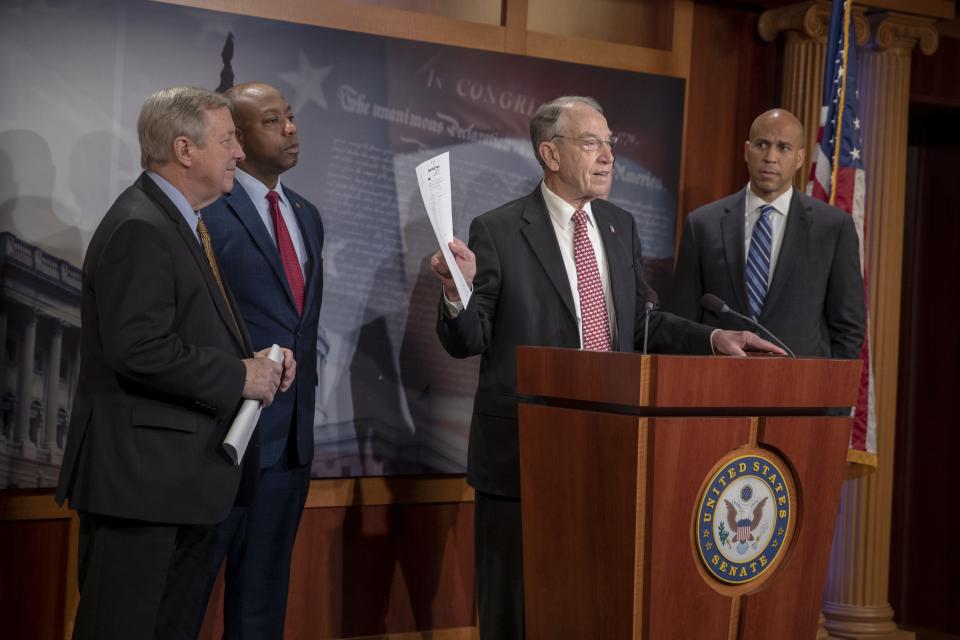

A companion legislation in the Senate has two Republican co-sponsors, Sens. Rand Paul, R-Ky., and Rob Portman, R-Ohio. Democrats need at least 10 Republicans to overcome a filibuster and bring the bill to a vote. A Senate Judiciary Committee Democratic aide said Sens. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., and Cory Booker, D-N.J., who sponsored the bill, are working to get bipartisan support.

Advocates look to Sen. Chuck Grassley, who has opposed mandatory sentences and supported reducing the disparity to 18:1, as someone who can convince other conservatives to get on board. But the Republican from Iowa has remained noncommittal.

During a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing last month, Grassley said "there are discrepancies between crack and powder cocaine in terms of recidivism rates, addiction, and violent crime. These factors can't be ignored."

George Hartmann, Grassley's spokesman, said the senator is open to reviewing the sentencing disparity to find a more fair ratio.

"He raised a variety of procedural objections, which allowed him to really signal, 'I don't want this to go forward,' or 'It's going to be hard to get me to support this … even if I don't want to flat out oppose it,'" Sterling, the former House Judiciary Committee counsel, said of Grassley.

Holly Harris, president and executive director of Justice Action Network, is more optimistic, citing support from Paul, Portman and Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson, a Republican, who endorsed the bill before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

"The EQUAL Act will pass, and history will smile on those who support it," Harris said.

Katharine Neill Harris, a drug policy fellow at Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy, said drug reform has become a bipartisan issue, but she fears it's been complicated by the politics around crime and law and order.

"We kind of beat this dead horse. Decades of evidence that the two drugs are chemically the same … when it comes to political rhetoric, the facts don't necessarily matter," Neill Harris said.

The bill, unlike other pending criminal justice legislation, is simple and narrow in scope, which could make it an easy sell to skeptics, but there's less political benefit to passing a small bill, said Sterling, the former House Judiciary Committee counsel.

"You would think this would be an easy lift, but that's not the case," said Maritza Perez, director of the Drug Policy Alliance's Office of National Affairs. "But we still have time, and we're not losing hope."

Kara Gotsch, deputy director of The Sentencing Project, said the EQUAL Act is an important, albeit small, step toward dismantling sentencing policies that disproportionately targeted Black Americans.

"For a lot of people, the punitive response to the war on drugs, which at the end of the day really is a health issue, was motivated by racism," Gotsch said.

"The people who have overwhelmingly experienced the burden of that are communities of color," she added. "We really need to see a reckoning on that, with this entire approach to drug use in the United States."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Joe Biden wants to close crack, powder cocaine sentencing disparity