The growing threat of political 'deepfakes'

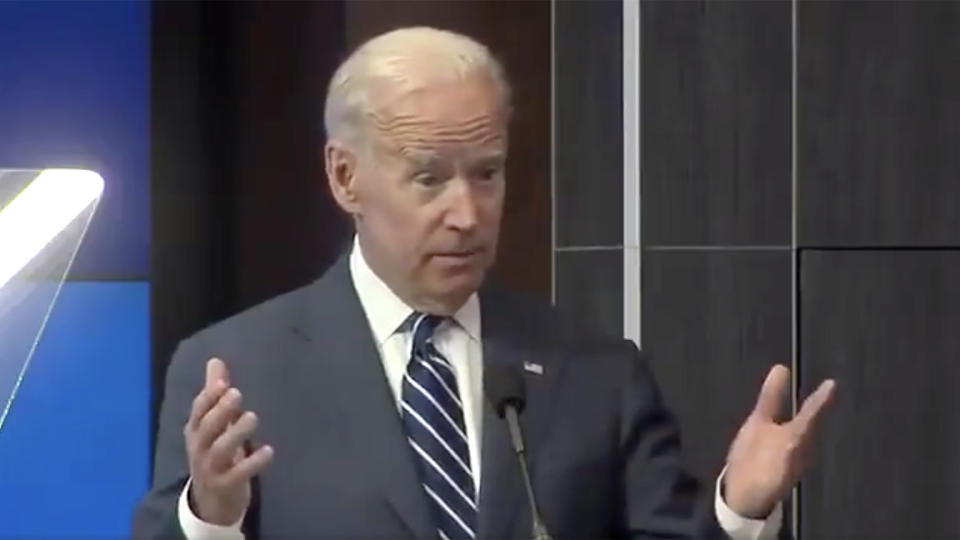

On the first day of 2020, a video of former Vice President Joe Biden circulated on Twitter. It appeared to show the presidential candidate agreeing with GOP proposals to cut Social Security benefits, a hot-button issue for Democratic primary voters.

Weeks after the video was posted by a Sanders campaign adviser, Biden publicly accused rival Bernie Sanders’s campaign of “pushing around a deceptively edited video.” PolitiFact concluded that the video clip was taken out of context to create a false impression — Biden was actually opposing cuts — but the footage was not faked or altered.

“PolitiFact looked at it and they doctored the photo, they doctored the piece and it’s acknowledged that it’s a fake,” Biden said Saturday about the video clip, excerpted from a speech at the Brookings Institution in April 2018.

“It’s simply a lie,” Biden said. “This is a doctored tape.”

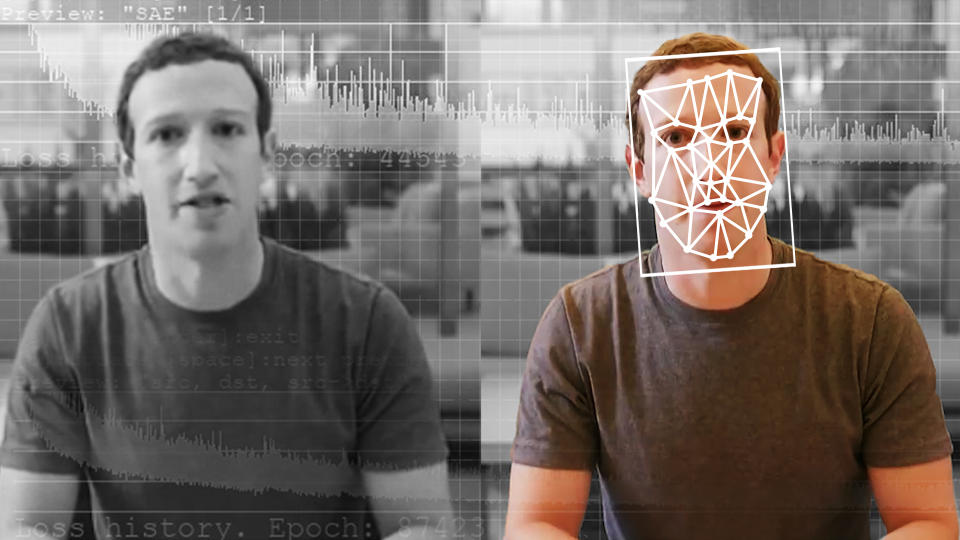

The larger point, aside from the semantic difference between a misleading tape and a doctored one, is the growing risk of so-called “deepfakes” — photos or video created or undetectably altered by technology — to spread disinformation and influence elections.

Last year, a doctored video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi altered to make her sound drunk or ill was viewed over 2 million times after it was posted to Facebook and shared by President Trump on Twitter. The video was relatively simple in its distortion compared to deepfakes synthetically created by artificial intelligence, but the speed with which it spread made it clear how unprepared some tech companies, news organizations and consumers were for the new technology.

“The Sanders-Biden dustup is a good illustration that you don't even need to have a full-fledged deepfake in order to potentially cause disruption or raise questions and so forth because you can use much cruder methods to distort video evidence,” Paul Barrett, NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights deputy director and author of its recent report on disinformation and the 2020 presidential race, told Yahoo News.

“Deepfakes are another step down the road on which we began with ‘fake news’ and show the continuing development of problems having to do with harmful content in general and misleading content in particular,” said Barrett.

The term “deepfakes” entered the mainstream about two years ago “when a Reddit user who went by the moniker ‘Deepfakes’ — a portmanteau of “deep learning” and “fake” — started posting digitally altered pornographic videos,” The Guardian reported in 2018.

That year, Buzzfeed, with the assistance of film director Jordan Peele, showed how easy it is to create a completely fake video of a famous person — former President Barack Obama, who was made to appear to be calling President Trump a “total and complete dips***.” The clip, which was an acknowledged fake and not intended to deceive, has received over 7 million views on YouTube.

“Deepfakes are kind of starting to take on the meaning of not just video, whereas it also kind of looks at audio, text and video in that all of these things can be generated by AI in a very methodical and targeted way,” Wasim Khaled, CEO and founding partner of Blackbird.AI, a software company that uses AI to combat disinformation, told Yahoo News.

But according to Khaled, these types of distorted videos have evolved from “advanced AI-generated face swapping technologies that people typically gravitate towards when they hear the word deepfake [to] what we would call ‘cheapfakes,’ which anyone can put together, like the Nancy Pelosi video.”

The video of Democratic frontrunner Biden, which Khaled said he would classify “as a cheap fake and doctored video not using advanced AI technology, just editing,” is an example of “an assault on the public's sense of perception.”

“The goal is to shift public perception about a person, about an event, about a policy perhaps,” he said. “If you can shift that public perception enough to create some sort of a public outcry, now you have the mainstream media attention as well as the authentic population on social media that believes something [real] is now happening.”

“And while the video is very powerful,” Khaled added, “how those narratives spread and why they’re being spread is critical to understand.”

“There are two potential ways that deepfakes could be a problem,” Barrett said. “The first is in the ‘October surprise’ scenario, where very close to the actual voting, you have a video that shows a candidate doing or saying something that they never did or said and because it’s so close to voting, there’s not enough time to adequately debunk it and it could affect some portion of undecided voters and actually tilt the election.”

It was the risk of that kind of attack that led Pete Buttigieg’s campaign to take the unusual step of documenting the candidate’s movements continually, compiling a record that could be used to discredit a faked video. “If there is that doctored video, we have that vision to kind of combat it,” Mick Baccio, the campaign’s chief information security officer said at a cybersecurity conference last November. “One of the problems we’re trying to get in front of is we keep [Buttigieg] in front of a camera pretty much all of his waking hours.”

The other problem with deepfakes, Barrett said, could be carried out “over the course of the election campaign — beginning now.”

“We would have a sufficient volume of distorted or manipulated video or still images,” he said, so much so “that people would grow cynical and apathetic in general so you'd end up with voters responding to all of this manipulated material by saying, 'I don't know what's true, I can't figure it out. They're all lying to me. I'm not even gonna vote at all.'”

The technology for deepfakes is becoming increasingly accessible from mainstream platforms such as Snapchat (whose developer, Snap Inc., purchased an image- and video-recognition startup recently) and TikTok, which is building deepfake technology to enable users to insert their face into scenes and videos starring someone else.

Amid fears that altered videos could influence the next presidential election, political and business leaders — even the military — have entered the fight to stem the disinformation threat of deepfakes.

Following the Pelosi video controversy, the House Intelligence Committee held congressional hearings to investigate deepfakes that “have the capacity to disrupt entire campaigns, including that for the presidency,” as stated by the committee’s chair, Rep. Adam Schiff.

Last fall, Califonia passed a new law, AB 730, which took effect on Jan. 1, making it illegal to distribute within 60 days of an election manipulated audio or video of a political candidate that is maliciously deceptive and “would falsely appear to a reasonable person to be authentic.” The law allows targets of deepfakes to sue the producers or distributors of the material.

But media experts argue such laws won’t stand up against free speech protections.

“Political speech enjoys the highest level of protection under U.S. law,” Jane Kirtley, a professor of media ethics and law at Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication, told the Guardian. “The desire to protect people from deceptive content in the run-up to an election is very strong and very understandable, but I am skeptical about whether they are going to be able to enforce this law.”

Barrett argued that “it's appropriate for governments to look at potential regulation” of deepfakes, but called it “a very tricky area because you get into government regulating content and you're in the realm of the first amendment. So you have to proceed with tremendous caution.”

The fight against deepfakes and other types of disinformation, he said, has to be “group effort,” but “social media companies have to take the lead on detection.”

“It's on their platforms that this kind of distorted material gets disseminated so widely and so quickly,” said Barrett. “And they are turning a profit on the provision of social media. So it's their responsibility to make sure that their systems are not exploited.”

Social media companies, facing rising pressure to prevent the spread of disinformation and deepfakes, have developed new policies for technology that enables anyone to manipulate images, audio and video online.

Facebook, which declined to take down the doctored video of Pelosi on the grounds that it has no policy stipulating that content “must be true,” launched a Deepfake Detection Challenge last year to “build better tools” to identify manipulated media. As a part of the challenge, the social media giant provided over 100,000 AI-manipulated videos to help researchers test their detection tools.

The platform came under intense scrutiny after the Mueller report on Russian meddling in the 2016 presidential election underscored misinformation campaigns carried out on Facebook and other social media sites by fake accounts connected to the Internet Research Agency (IRA), also known as the Russian troll farm. Facebook had estimated that IRA-controlled accounts reached up to 126 million people.

Since this revelation, the company has taken measures to combat disinformation leading up to the 2020 election, including purging accounts that used AI-generated profile photos and clearly labeling content deemed false by independent fact-checkers.

“We know that our adversaries are always changing their techniques so we are constantly working to stay ahead,” a Facebook spokesperson wrote to Yahoo News in an email. “We’ve developed smarter tools, greater transparency, and stronger partnerships to better identify emerging threats, stop bad actors, and reduce the spread of misinformation on Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp.”

“Protecting the integrity of elections is one of Facebook’s highest priorities,” the statement read.

But Facebook is keeping its policy of not fact-checking political ads, despite growing public pressure to not allow false information by candidates.

“The Facebook business model is strictly to make money,” Pelosi said at a press conference last week. “They don't care about the impact on children, they don't care about truth, they don't care about where this is all coming from, and they have said even if they know it's not true they will print it.”

“I think they have been very abusive of the great opportunity that technology has given them,” she added. “They intend to be accomplices in misleading the American people.”

According to the NYU disinformation study, 64 percent of Americans believe the platform is at least “somewhat” responsible for spreading disinformation (compared to 55 percent for Twitter and 48 percent for YouTube).

But some experts downplay the danger.

“Technology-driven deepfakes are not as big a threat in 2020 elections. The tech is not there to get as widespread use,” argued Khaled.

While he considers deepfakes “one of the fastest progressing disinformation technologies and a breakthrough away from being a major threat in the near future,” Khaled also pointed to less expensive and widely available means of creating and distributing manipulated content.

His advice to campaigns: “The biggest thing they actually need to be focusing on this year is the disinformation on text-based content and how those are amplified.”

Wasim continued: “The fact is, for the types of deepfakes that are most harmful, it's really computationally heavy and requires significant resources or know-how. And the benefits of that approach is really not nearly as damaging as, say, ‘Let’s fire up hundred blogs and let's get 20,000 Twitter accounts to now tweet these different articles that we wrote up for a particular narrative and then [tag] all of the people who we think are going to amplify it, be it a Congressman, be it an influencer or be it another account with a million followers.’”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

The inside story of how the U.S. gave up a chance to kill Soleimani in 2007

Yahoo News/YouGov poll shows two-thirds of voters want the Senate to call new impeachment witnesses

Steyer: U.S. reparations for slavery will help 'repair the damage'

As Trump impeachment trial nears, the battle turns to witnesses