The U.S. has held an election during a pandemic before. Here’s what happened in 1918.

This is part of an occasional series of Yahoo News articles and accompanying videos on how the issues America faced in the 1920s — aka “the Roaring Twenties” — have echoes in our own decade, a century later.

Like almost everything else in 2020, Election Day this year will look very different as Americans head to the polls — or in many cases, their mailboxes — to cast their ballots. With the White House and Senate majority up for grabs, high-stakes elections are taking place nationwide in the midst of a global coronavirus pandemic that has so far infected over 8.3 million and killed more than 221,000 in the United States alone.

Yet while voting during a deadly pandemic is certainly unusual, it’s not totally unprecedented.

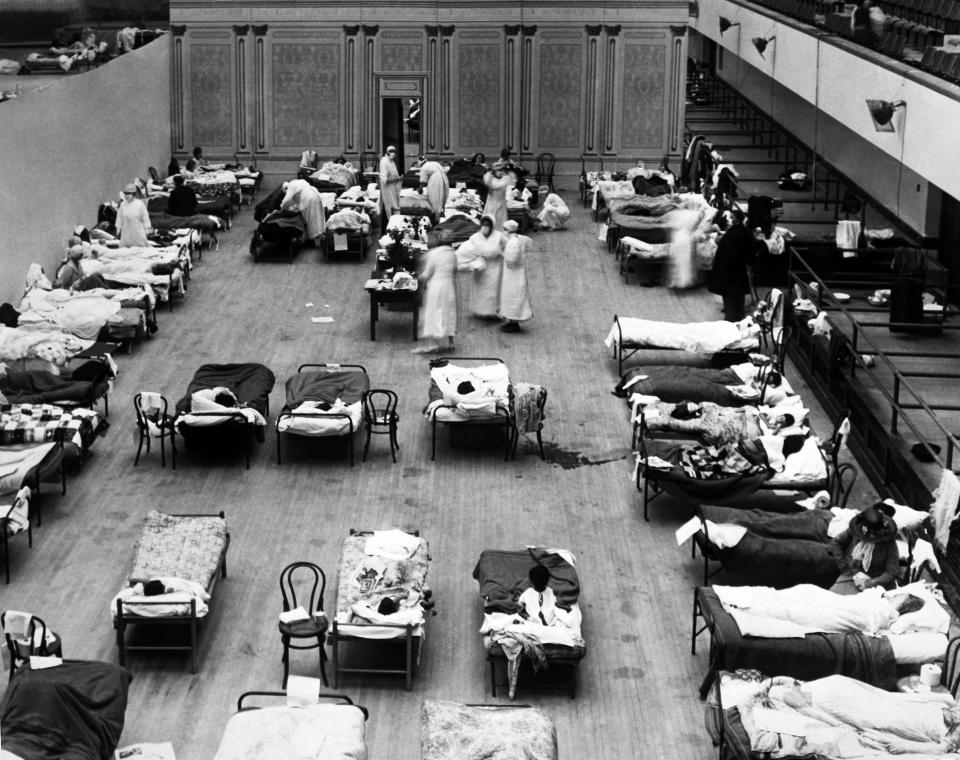

During the peak of the so-called Spanish influenza pandemic in the fall of 1918, midterm elections took place, with President Woodrow Wilson’s Democratic Party fighting to keep control of Congress. And like today, these were strange times (The Oakland Tribune called it one of the “queerest elections in history of California”), with campaigns scrambling to adapt to localized mask mandates and bans on public gatherings. Candidates relied on local newspaper publicity, personal letters and house-to-house canvassing. Billboards became a popular way to get the message out, for those who could afford it. One newspaper, noting “the orders prohibiting meetings,” observed that “letter writing, advertising and telephoning” had taken the place of “speech-making.”

The haphazard manner in which Spanish flu restrictions were implemented sometimes contributed to some inter-party bickering. Democrat Alfred E. Smith was running against Republican incumbent Charles Seymour Whitman for governor of New York when one of his events upstate was abruptly canceled due to Spanish flu concerns. Democrats complained of a “Republican quarantine against Democratic campaign speeches,” and Smith accused Republicans of using the pandemic “for political ends,” saying in a statement that “in spite of the fact that there is very little evidence of epidemic in that city, as the schools, churches, and places of amusement are open, the Board of Health or the local health authorities, all Republicans, met last night and declared against our meeting, but left all other gatherings alone.”

“What is becoming of the good old American theory of fair play?” Smith lamented.

It’s unclear whether there was any merit to Smith’s accusations; both campaigns would end up encountering pandemic-induced snags with campaign events upstate. But Smith would ultimately come out on top, beating Whitman to become governor of New York for four terms, and becoming the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

Jason Marisam researched the pandemic’s effects on the 1918 election as a legal fellow at Harvard Law School, and now works as an assistant attorney general in Minnesota.

“They really had to resort to using flyers and mailings, newspaper ads,” Marisam told Yahoo News. “And it really did change the nature of the campaign. The candidates couldn’t rely on the local rallies that they’d been used to, and they didn’t have the social media and technology that we have today.”

Although President Trump has chosen to continue his favored large-scale in-person rallies — despite testing positive for the virus himself — politicians today have certainly utilized some invaluable campaign tools that weren’t available to flailing pandemic-era campaigns in 1918. Candidates can court voters and conduct media interviews from the safety of their basement.

This year’s Democratic National Convention was held virtually, while Republicans opted for a hybrid of in-person and virtual events at the RNC.

And the 2020 election has another major edge on 1918: mail-in voting.

A new Yahoo News/YouGov poll found that less than a third of U.S. voters plan to cast their ballots in person on Election Day — the lowest percentage in American history. Forty-two percent said they planned to or already had voted by mail, and 22 percent planned to vote in person before Nov. 3 or had already done so.

But that wasn’t the case 100 years ago.

“Ability to vote by mail was quite limited,” Marisam said. “You didn’t have the sort of absentee system that a lot of states have today. Your choice really was, show up to the polls on Election Day or don’t vote. And that probably did have an impact on turnout. The numbers suggest it had some impact.”

In 1918, voters’ experiences on Election Day varied. With no nationwide pandemic strategy, there was a patchwork of different strategies implemented by different cities and states. And Spanish flu was on the rise in some places and waning in others; the virus had peaked on the East Coast in October, but by Election Day was wreaking havoc on the West Coast.

“In San Francisco, there was an ordinance requiring people to wear masks, so they had all the voters lining up wearing masks,” Marisam said. “The San Francisco Chronicle called it ‘the first masked ballot’ in U.S. history.”

In Oakland, Calif., newspapers noted that all polling places remained open but were short-staffed because “many of those selected as election booth officials have been made ill by Spanish Influenza and substitutes have been difficult to obtain by reason of fear of the epidemic.”

Those who were bedridden or under quarantine often weren’t able to vote at all.

The case of Harper v. Dotson highlights the challenges those under quarantine faced. When a group of students and teachers quarantined at a school in Idaho weren’t allowed to leave campus to vote, they convinced county officials to set up a last-minute precinct at the school so they could cast their ballots. But those ballots were soon challenged.

“We wouldn’t have heard about this at all — it wouldn’t be preserved, really, in the historical record in an easy-to-find way — except that the votes cast at the school turned out to determine the outcome of a local probate county judge election, which led to litigation,” Marisam explained of the case.

Ultimately, the Idaho Supreme Court ruled that the votes cast at the school weren’t valid because the new voting precinct hadn’t been set up early enough.

“It wasn’t as if new precincts were available to every Idaho voter who might not have been able to leave their house,” Marisam said. “So that was the problem I think the court was concerned about.

“What that highlights, though, is you don’t want people to lose the ability to vote, lose the fundamental right to vote, because of the pandemic,” he continued. “And you’ve just got to make sure that you have the election administration in place, that you can ensure that people can vote, but in a way that complies with notice and fairness.”

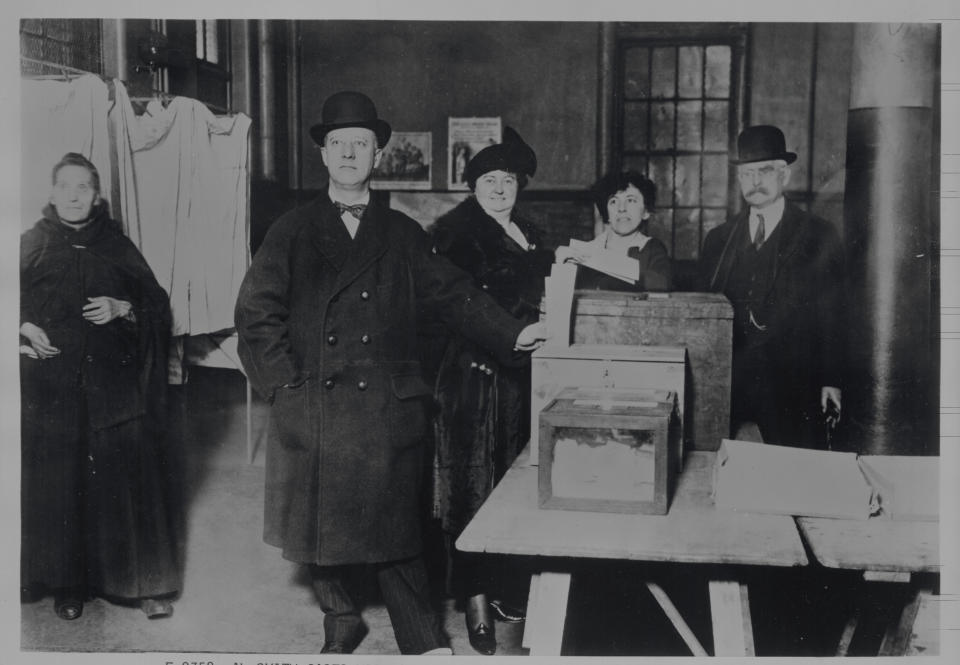

There were some new voters that election cycle; in states like New York, which had just passed statewide suffrage, women were heading to the polls for the first time two years before the 19th Amendment would give women the right to vote nationwide.

Still, national voter turnout in 1918 was 10 percent lower than the previous midterm election, with a total of 40 percent of eligible voters showing up at the polls. A year later, the New York Times would observe that “the influenza pandemic kept many voters at home on Election Day.”

While the pandemic had an impact on voter turnout, there were likely other forces at play as well.

Much of the U.S. — and the world — was focused on World War 1. And although the war was winding down and would end days after the U.S. elections, with Germany signing an armistice agreement that took effect on Nov. 11, there was no regular procedure to provide for soldier voting. War workers in munitions plants or shipyards far from home likely also contributed to a decrease in votes.

Midterms have also traditionally had lower voter turnout than presidential elections. The 2018 midterm, which was widely acknowledged for its unusually high voter turnout, saw 53.4 percent of eligible voters participate — nearly 12 percentage points higher than the previous midterm in 2014, where 41.9 percent of Americans voted.

“It wasn’t a presidential election, so it didn’t have a lot of the same magnitude,” Marisam observed of the 1918 election. “Certainly, it was an important midterm. Control of Congress ultimately flipped from the Democrats to the Republicans for the first time in about a decade. And Woodrow Wilson was in his second term, and some people might have been voting in sort of a rebuke to the incumbent.”

“But even with turnout being down a little bit,” Marisam added, “it was certainly high enough that there was no public discussion casting doubt on the legitimacy of the results because of the pandemic.”

We’re unlikely to be so lucky this time around. According to a Reuters/Ipsos poll released July 31, about half of registered voters, including some 80 percent of Republicans, said they were concerned that an increase in voting by mail will lead to widespread fraud, suggesting that much of the country may have trouble accepting the result of the election.

President Trump has for months been sowing doubts about mail-in voting with baseless claims of “voter fraud,” setting the stage for a possible contested election whose results could be in doubt well beyond Nov. 3.

“Usually at the end of the evening, they say ‘Donald Trump has won the election, Donald Trump is your new president,’” Trump said during a press conference in August.

“You know what? You’re not going to know this — possibly, if you really did it right — for months or for years. Because these ballots are all going to be lost, they’re all going to be gone.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: