The Occidental-Anadarko Petroleum Merger's Crude Truth About Oil Prices

On the last Friday in April, Warren Buffett got a call from Brian Moynihan, the CEO of Bank of America, asking if he would back Occidental Petroleum’s underdog bid for rival oil driller Anadarko. Two days later, Occidental CEO Vicki Hollub was making the pitch herself, having flown to Omaha to appeal directly to the world’s most famous invest or. It took Buffett only an hour to say yes.

That Sunday, the Berkshire Hathaway CEO promised $10 billion in financing to Occidental if Hollub could get the deal done. There was, of course, one complicating factor: Anadarko had already pledged to sell itself to oil giant Chevron and would owe the latter $1 billion if it broke their engagement. What followed was a remarkable coup d’état in America’s own oil-soaked Emirate—the famous Permian Basin that stretches 86,000 square miles from Texas to New Mexico—and it all happened in hyperspeed.

Just a week and a half after Buffett and Hollub’s meeting, a bidding war that had played out in daily headlines was over: Chevron (No. 11 on this year’s Fortune 500) walked, and Occidental (No. 167) announced it would buy Anadarko (No. 237) for a total price tag of $57 billion including debt. It’s the largest U.S. oil and gas merger in more than 20 years (since Exxon bought Mobil) and would catapult the combined company into the Fortune 100 elite.

Buffett, in an interview discussing his investment, told CNBC, “It’s a bet on oil prices over the long term more than anything else.” Yet notably, what he didn’t say was whether he was betting on oil prices to be higher. (He declined to comment to Fortune for this story.) “It’s also a bet on the fact that the Permian Basin is what it’s cracked up to be,” Buffett added during the TV segment, without elaborating.

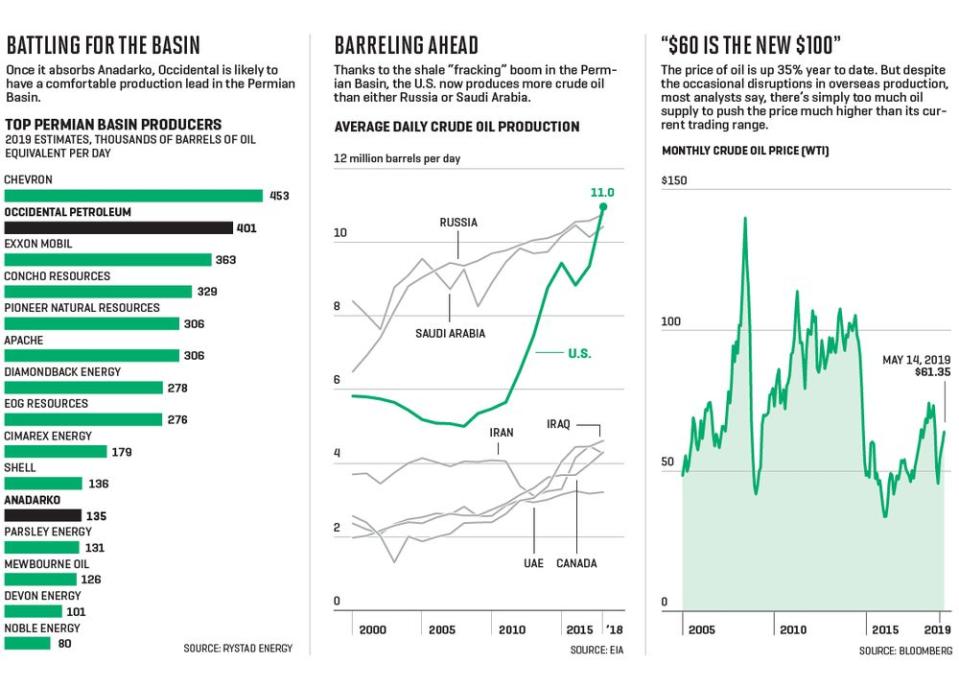

Of course, what the Permian is—quite literally—cracked up to be is one of the biggest oil reserves America has ever known. And it has made the U.S. the top oil-producing country in the world. Its thick shale deposits, hydraulically fractured and pumped for oil, have attracted not only Chevron, Occidental, and Anadarko, but also hundreds of other drillers, which have claimed a big chunk of West Texas (as well as a corner of New Mexico). The “fracking” boom, as it’s known, is responsible for pushing U.S. crude production to a record of roughly 11 million barrels a day in 2018, surpassing Saudi Arabia and Russia for the first time since the end of the Cold War. As of the latest monthly data, the Permian alone produces more crude per day than the United Arab Emirates, Canada, or Iran; by next year, some expect it could also outpace Iraq, which would make the southwestern region the fourth-largest oil producer in the world, if it were its own country. “The Permian is the absolute 800-pound gorilla for shale,” says Mike Morey, CIO of Integrity Viking Funds, who runs a top-performing energy stock fund.

The Permian is also one of the cheapest places to drill for oil, not only in the U.S., but in the world. Unlike costly deepwater and offshore rigs, drillers can make money on Permian oil as long as it trades for at least $50 a barrel. That’s made the region an oasis for energy companies that have struggled ever since 2014, when West Texas crude prices collapsed from a peak of $107. In the years since, prices have never come close to reaching triple digits and have dipped as low as $26 a barrel.

So far this year, prices have generally been on the upswing, and are up some 35% in 2019—to around $62 per barrel—despite concerns that a continuing trade war with China will slow demand. Still, it’s hard to find a bull who thinks that oil has reason to rise much more. “Short of a real sustained geopolitical event—not the periodic flashes that have been impacting the markets—I don’t know that anybody thinks that there’s an upside for commodity prices themselves,” says longtime energy economist Michelle Michot Foss, a fellow at the Center for Energy Studies at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

Indeed, even with production disruptions resulting from the reactivation of Iran sanctions in May—as well as turmoil in other OPEC exporters like Libya and Venezuela—the Permian has created such an abundance of supply that it can quickly make up for lost inventory. In the years between 2009, when the Great Recession ended, and 2014, there’s been a paradigm shift in the industry, says Devin McDermott, an equity analyst at Morgan Stanley: “We’ve gone from a decade of resource scarcity, and the focus on peak oil supply—‘when do we run out of oil?’—to more oil than we need.” What’s more, there’s enough still in the Permian ground to last at least the next 20 years.

Now, after generations of seesawing crude cycles, companies are wondering whether the best they can hope for, in terms of prices, is flat. “The industry is realizing they can’t count on higher prices,” says Dan Pickering, president of Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co., an energy investment bank headquartered in Houston. He expects oil to trade between $50 and $75 a barrel for the foreseeable future. After all, he says, there are also political forces at play—with, on the one hand, the OPEC oil cartel ready to slash output if prices fall to unprofitable lows, and on the other, President Trump determined to ensure gas stays cheap to fuel the U.S. economy. “My view is, we’ve determined the price range for crude: OPEC is cutting production at $50, and Trump is tweeting at $70,” adds Pickering. Since taking office, Trump has tweeted increasingly often about oil and gas prices—eight times so far in 2019, and three in April alone—generally calling on OPEC to pump more supply to market.

The price may not exactly be a gusher, but the drillers are figuring out how to live with it. In the past six months or so, U.S. energy companies have trimmed capital spending, and cut down on the number of rigs, boosting their profitability and allowing them to retain more of their cash flow. “We kind of use the phrase ‘$60 is the new $100,’ ” says Jonathan Waghorn, a onetime Shell drilling engineer who is now a portfolio manager for Guinness Atkinson.

The irony is, the good ole days for the oil patch weren’t exactly that. Even when oil was $100 a barrel a few years ago, companies weren’t as profitable as they should have been, says Waghorn. In those heady days, and until last year, U.S. oil and gas exploration and production companies paid out more on capital expenditures and dividends than they had in cash flow, according to Morgan Stanley—and S&P 500 energy stocks have been consistent underperformers since the start of the shale oil revolution. “If we were looking into your crystal ball at this supernova birth [of shale] in the U.S., I think you would have surmised that these stocks would have done exceedingly well, but they haven’t,” says Bill Herbert, managing director and senior research analyst at Simmons Energy, the oil and gas investment banking arm of Piper Jaffray.

For years, the sector burned so many investors that many abandoned it. But the Occidental deal may have reignited interest. It’s funny what $10 billion from Warren Buffett will do.

Which brings us back to Occidental’s all-in, table-clearing bid for Anadarko, and the hunt for scale in the Permian. In the past few months, Occidental nudged past the much-larger Chevron to become the top Permian oil producer, but it was going to be hard to stay there: Chevron was rapidly upping its Permian ambitions, and had recently promised to grow its production there 53% by 2020.

That’s why Chevron wanted Anadarko, too. The notion of marriage between the two oil producers promised some unique advantages: The parcels each company controls in the Permian run along the old Texas & Pacific rail line, meaning a merger would have united the land like a massive checkerboard, lowering costs further. Rival Occidental would be boxed out.

On its own, Occidental would likely find it nearly impossible to hang on as the region’s top producer. That’s why it, too, had been coveting Anadarko—and indeed had been in talks with the company over a potential deal for almost two years. When Chevron announced its agreement to purchase Anadarko in mid-April for $50 billion including debt, Occidental found itself between tight rock and a hard place: If it wanted Anadarko, it would have to somehow break up the Chevron deal and cover its billion-dollar dowry.

In the Permian Basin, there’s virtually no risk of wasting money on “dry” wells because everyone knows that oil is in that “tight rock,” as the shale formations are known. The proximity to the Gulf Coast also makes it convenient for companies to get the crude to market—especially now with new pipelines opening up. “This is really just an ideal situation for companies in a great number of respects,” Foss says. “They’ve got a complete value chain from field to market, and with coastal access for exports right in the United States. They haven’t had that for 30 to 40 years.”

By gobbling up Anadarko, Occidental would get to solidify its position in this golden region even more. That said, it’s paying a mighty big premium—$11 more per share than what Chevron offered. And in exchange for his $10 billion, Buffett has received 100,000 preferred shares in Occidental , with an 8% annual dividend. Not everyone thinks the price is justified. Occidental’s stock plummeted 13% in the three weeks after it went public with the Anadarko bid, with its own shareholders criticizing the high cost of the purchase and the fact that Buffett got the sweeter end of the deal. T. Rowe Price, which holds 2.8% of Occidental shares, had (unsuccessfully) threatened to oust the company’s board of directors at its May shareholder meeting, complaining that management should have let shareholders vote on the merger.

“We view the Permian as Occidental’s crown jewel,” says John Linehan, chief investment officer of equity at T. Rowe Price, adding that Occidental’s assets here were the “core reason” he invested in the company in the first place. But the Anadarko deal, oddly enough, dilutes that rationale. While the combined company will have more acreage in the Permian Basin, he says, its overall production will be less concentrated there, because Anadarko has a larger share of its output outside the region. “This isn’t the race to be the biggest,” says Linehan. “It’s the race to have the best total returns.”

“We know the Permian. It’s the foundation of our company,” says Occidental CEO Vicki Hollub in a statement to Fortune. “But it’s not size that matters to us. What really matters to us is not to be the biggest but to be the best. And I think we’ve proven that.” With regard to bypassing a shareholder vote on the deal, Hollub said on a recent earnings call that the company did so to ensure that it “had a reasonable chance to make this happen,” as the Chevron agreement did not require a vote. “We weren’t playing on a level playing field,” she said.

Chevron, on the other hand, is no worse for wear without Anadarko. “There are plenty more fish in the sea,” says portfolio manager Waghorn. “There’s no particular reason that Anadarko should stand out.” In fact, now that the major oil conglomerate has tipped its hand in terms of its acquisition appetite, a slew of Permian producers look like potential targets. Analysts are eyeing Pioneer Natural Resources, Noble Energy, Apache Corp., Concho Resources, Parsley Energy, and Diamondback Energy, among others, as takeout candidates. “I think we’re probably one deal away from a big consolidation wave,” says Pickering. “If we see Exxon, Shell, BP, or Total do another big transaction, I think there will be a huge rush to find your dance partner, and there will be a significant amount of fear of missing out.”

The signs of an imminent M&A wave in the still-nascent fracking industry remind Pickering, the investment banker, of the dotcom boom of the late ’90s. Back then, investors chased high growth, throwing money at companies despite their lack of profits—before the market crash ultimately forced a consolidation of Internet startups. “That’s happening in the oil patch now,” Pickering says.

Inevitably, U.S. oil production growth, on the whole, will slow, as companies pull back on drilling. The trick for them, if oil prices do ultimately rise, will be not ramping production back up too aggressively, such that prices collapse again. “Hopefully this time the industry learns its lesson,” says Integrity Viking’s Mike Morey.

After all, Permian producers themselves may have an incentive to keep supply—and prices—in check. Because they can make money on cheaper oil than many drillers outside the U.S. can, they face less competition when prices are low. If the price of oil were to rise to $80 a barrel, more foreign competitors would start pumping too, says John Musgrave, portfolio manager and co-CIO of Cushing Asset Management. “Theoretically, you almost wouldn’t want crude oil prices to skyrocket higher.”

As for Buffett, he’s going to make money no matter where oil prices go, thanks to his preferred shares. That may be the most profitable move in the oil patch in years.

This article appears in the June 2019 issue of Fortune with the headline “The Queen of Texas Hold ‘Em.”

More must-read stories from Fortune:

—The 2019 Fortune 500 list demonstrates the prize of size

—The Fortune 500 has more female CEOs than ever before

—Fortune 500 CEO Survey: The results are in

—What the Fortune 500 would look like as a microbiome

—Why the giants among this year’s Fortune 500 should intimidate you

Sign up for The Ledger, a weekly newsletter on the intersection of technology and finance.