Citizenship question on 2020 census a 'surveillance system,' critics say

The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to rule soon on the Trump administration’s plan to include a citizenship question on the 2020 census, but experts believe its addition would have dire consequences for communities with large numbers of immigrants.

“This question also could set off a lot of insecurities and distrust that certain populations have currently of the U.S. government,” Jennifer Van Hook, a sociology and demography professor at Pennsylvania State University, told Yahoo News. “Because it sounds like somebody’s looking into their citizenship, wondering if they belong in the United States, raising fears that the information they provide to the census could then be passed along to law enforcement agencies or ICE, and then be used to either target them or people that they know in their community.”

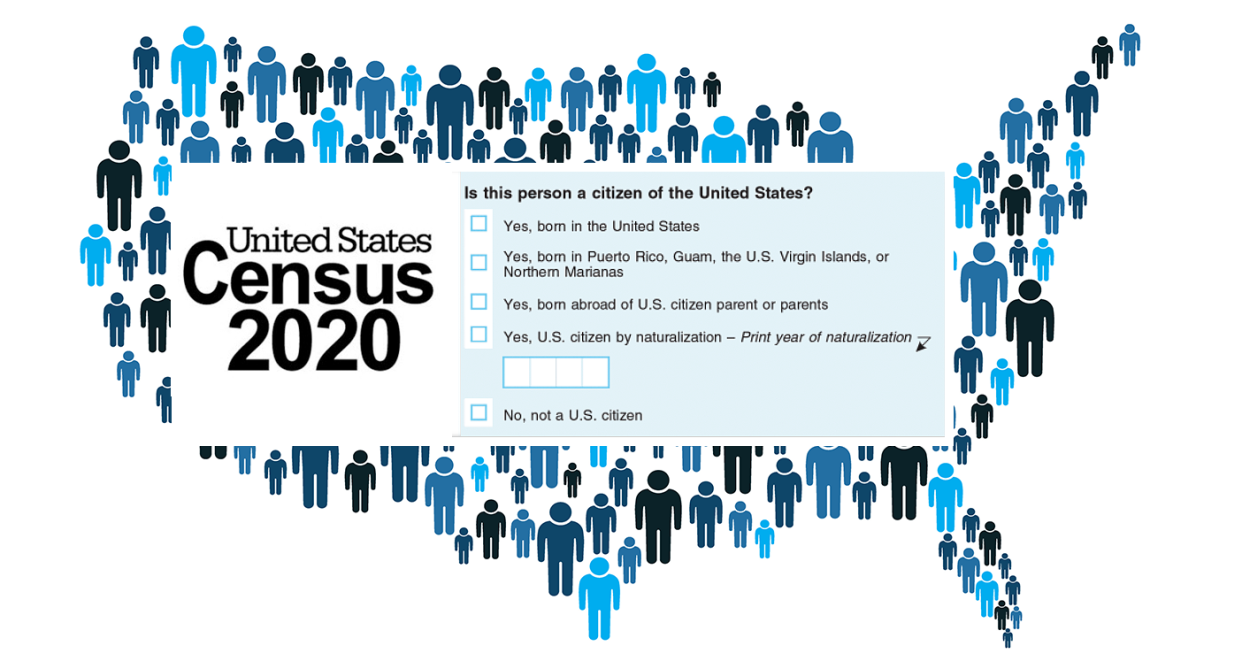

The census hasn’t asked about citizenship since 1950, but as of last week, the Supreme Court will decide whether the 2020 census will include the question “Is this person a citizen of the United States?”

In January, about five months ahead of this summer’s printing deadline, Manhattan District Judge Jesse Furman ordered the Department of Commerce to remove the citizenship question from the 2020 census, adding that it was “unlawful for a multitude of independent reasons.” But when the Trump administration filed an appeal and requested that the Supreme Court weigh in on a dispute about evidence, the high court stepped in, bypassing what would likely have been a lengthy federal appeals court process.

Van Hook believes the question has no place in the census.

“The decennial census is not designed to collect information about the composition of the population. The chief focus is to get a head count of the population,” Van Hook said. “We have other surveys to collect information about the characteristics of the population, including citizenship status.”

The idea of including a citizenship question has long been controversial. When Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross, who oversees the Census Bureau, announced last March that the citizenship question would be added to the census, there was an immediate outcry. Seventeen states and the District of Columbia filed a lawsuit against Ross and the Department of Commerce.

For over 200 years, the decennial head count of every person living in the U.S. — citizens and noncitizens — has helped states determine how funds, now hundreds of billions of dollars, are allocated according to population size. The 2020 census, which begins on April 1 of next year and ends that summer, before congressional reapportionment and redistricting, also helps determine the allocation of House of Representatives seats and Electoral College votes.

Ross, who said the Department of Justice requested the citizenship question, justified its addition as a means to obtain an accurate count of the voting-age population and enforce a section of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which protects against voting discrimination. However, it was revealed in court documents released by the Trump administration that Ross sought to have the question added prior to receiving and approving the DOJ request, allegedly violating federal rules and procedures.

Former Census Bureau Director John Thompson, who reviewed the district court ruling against the Department of Commerce, told Yahoo News that he was never made aware that Ross had talked about adding the citizenship question.

Thompson also noted the bureau’s own assessment about respondents’ concerns around confidentiality.

“The Census Bureau has done its own research that shows that the citizenship question will reduce self-response among the noncitizen population,” Thompson said.

Thompson pointed out a larger issue with the citizenship question: the follow-up process. Noncitizens who don’t respond to the census can expect a census worker at their door, considering that after the last census, the bureau hired over 600,000 employees to visit about 50 million addresses up to six times each, according to the Government Accountability Office, which has already declared the 2020 Census a “high-risk” project “vulnerable to waste, fraud, abuse, and mismanagement.”

“After they’ve made a specific number of visits, if you can’t find anyone that could respond for the household directly, they will try to find a knowledgeable surrogate,” said Thompson. “In some cases, it would be neighbors. In some cases, it would be maybe an apartment building supervisor or some other source. The guideline is to try to find a knowledgeable source.”

But Thompson, who lives in Oregon, said proxy information is well known not to be as accurate as self-reported data.

“My neighbors don’t know my age,” Thompson said. “They can only guess at my race by my physical appearance. We’ve never talked about that. And they don’t know if I’m a citizen or not a citizen.”

Beyond the census, smaller surveys like the American Community Survey, which is sent out yearly to one in six U.S. households, ask about citizenship.

A smaller, more detailed questionnaire, the American Community Survey takes on average 40 minutes to complete, Thompson said, adding that it has “worked fine to support voting rights under multiple administrations, both Democrat and Republican.”

Kenneth Prewitt, who served as Census Bureau director from 1998 to 2001, agreed that the survey is sufficient in gathering information on citizenship, and called the rationale for including a citizenship question in the census “simply false.”

“We have good data that has been used for the last decade or more very successfully [through] the American Community Survey,” Prewitt added.

Prewitt told Yahoo News that the citizenship question on the census “feels like a surveillance system, not a census system.”

“If it is on the form, combining it with some other data that we have about citizenship drawn from administrating records, it allows you to construct a register of everyone who is a citizen and noncitizen in the country,” he said.

There is cause for privacy concerns, despite the fact that according to the “72-year rule” a respondent’s information can’t be made public until 72 years after it’s been collected. But in the not-so-distant past, the Census Bureau shared data with the military for the draft during World War I and gave Japanese-Americans’ information to the Secret Service during World War II.

“If you are an immigrant, an undocumented immigrant, or if you’re a U.S. citizen who is married to an immigrant or is part of a mixed-status family, you’re going to think twice before answering that question on your census form because the government will have that information,” said Ali Noorani, executive director of the National Immigration Forum, an advocacy organization in Washington, D.C.

It is this hesitancy, and overall resistance to take the census, that civil rights groups fear will have a ripple effect throughout vulnerable communities. States with large immigration populations, such as California, New York, Texas and Florida, all of which filed suit against the Department of Commerce, stand to be most affected if noncitizens decide not to take the census. But Noorani said they’re not the only ones.

“It’s the states in the Southeast and the Midwest, which have seen fast growth in the immigrant population, that really depend on a full and fair census count,” said Noorani. “Federal funding for highways and schools are determined in large part by the census, so if you’re a rural suburban school district in the middle of the country who is benefiting from a growing immigrant population, you want every one of those kids and families counted.”

States like California, Noorani said, are spending upwards of $100 million in state money to ensure a full count. “States like Nebraska, they don’t have those kinds of resources,” he added.

“All communities would be hurt,” said Beth Lynk, director of the Census Counts Campaign at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. “Having an unfair count and an inaccurate count of the census will negatively impact the ability of the federal government to distribute federal funding for key programs and will disproportionately impact key communities that are traditionally harder to count, like communities of color, immigrant communities, low-income communities, indigenous communities, communities that have young children and more.”

But Steve Camarota, director of research for the Center for Immigration Studies, said there’s a “big advantage” to having both noncitizens and citizens counted. “We would now add foreign-born to the [follow-up] work,” said Camarota, who was the lead researcher on a contract with the Census Bureau examining immigrant data in the American Community Survey. “From a researcher’s point of view, that would be incredible to be able to say, a little more definitively, how big is this undercount.”

Still, Camarota said he understands the controversy that the proposed inclusion of the citizenship question is causing. “Everyone has a suspicion here,” he said.

Democrats worry that the question is designed to “get people not to respond or hold down the representation of people who tend to be sympathetic to the Democratic Party,” he said.

As for Republican concerns, Camarota said the citizenship question could show that a “significant number of people who aren’t supposed to vote and register are doing so” and could “tell you exactly what the distribution of seats in the House of Representatives or in the state legislature in California would have been had you not counted all those noncitizens.”

While critics fear the inclusion of a citizenship question will result in a massive undercount, Camarota thinks that may be overblown.

“If you look at the American Community Survey, with the rise of Trump, we didn’t see a big drop-off [in participation]. It’s true that people are less willing over time to answer that question, but they’re also less willing to tell us whether they’re married, how much money they make.”

Starting in June, about half a million households will receive a test questionnaire that contains the citizenship question, because survey changes are required to be tested. In the meantime, the Supreme Court will hear arguments for the question’s ultimate inclusion in 2020.

“We are very, very fearful that there would be an undercount that would render our community more invisible if the citizenship question is allowed to stay on,” John C. Yang, president and executive director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice, told Yahoo News. “There is very heightened fear in our community already about the federal government and about privacy, and the citizenship question simply exacerbates it.”

Yang said the Asian community in the U.S. is made up predominantly of immigrants or the children of immigrants, and when asked if they will still take the census if the citizenship question remains, he said, “We want to ensure that there’s a fair, accurate count, but we also want to make sure that our community feels protected and feels safe.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Ann Coulter: ‘Lunatic’ Trump could be challenged in 2020 — from the right

As concerns grow about faltering U.S. support for UAE, China steps in to fill the void

Habitat for sale: An oil and gas group calls the tune at the Interior Department

Crackdown on opioids has its own victims: People who need them to live

As 5G war with China heats up, could a Cold War-inspired plan be the solution?

PHOTOS: Eye in the sky: Unusual shots of animals from above will leave you in awe