One shining moment: Reliving clinching out of World Series not getting old for Sergio Romo

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. – Sergio Romo would push play, just to remind himself it really was him.

He'd push play and feel the night air in Detroit. Push play and shake Buster Posey into that fastball, the final pitch of 2012. Push play and see the mitt and feel the baseball come off his fingers, maybe just off center, so the fastball – at 89 mph all his frail body could generate – ran to the middle of the plate. And the faces. All those happy faces.

Then he'd look at his son, 6-year-old Rilen, and nod to the television, almost as if he needed confirmation.

"Who's that, mijo?"

"That's you, dad."

Five sliders he'd thrown to Miguel Cabrera, the best hitter in the game, using the grip his own father had taught him in college. The fastball – the grip, the will behind it, the choice to throw it then and there – was all his.

In the 10th inning of Game 4 of the World Series, Sergio Romo would trust the fighter in himself and the journey to that moment. He'd been a junior-college pitcher, then transferred to a Division II school. He'd been drafted in the 28th round, 852nd overall, in 2005. He was too small. He didn't throw hard enough.

His father, Francisco, had told him, "Never take for granted what you know is achievable, never attainable."

They were driving from Brawley, Calif., where Sergio was raised, to Phoenix for his first minor-league spring training. Many had covered those miles, Francisco said. Baseball was achievable, this was proof of that. But, attainable? That was for Sergio to decide. He would have to work for it. Believe in it. Trust that good things awaited.

"To be honest," Sergio said, "I was just kind of tired of people calling me a punk all the time."

[Also: College baseball umpire takes embarrassing tumble (video)]

Romo had saved Games 2 and 3 of the World Series, both with two-run leads. The San Francisco Giants led the series, three games to none. While that might appear secure to most, if the Giants lost Game 4, they would get Justin Verlander in Game 5, and then there'd be no telling. No, they'd have get it done in the chill and howling wind at Comerica Park, in extra innings, holding a 4-3 lead, the rain coming. Sharpen the knife, leave Verlander on the bench, get out of town. That was the plan.

Along came Romo one more time. He was the closer because Brian Wilson blew out his elbow and Santiago Casilla couldn't hold the job. He liked to think he'd never taken a second in that Giants uniform for granted, so much so that he'd sobbed after games that clinched the NL West, the division series and the league championship series. Now he'd be on the mound, two out, Cabrera waving his bat, what was left of the spirit of Tigers fans in his ears. Those five sliders got him to a 2-and-2 count, the fifth of which Cabrera fouled with a swing that suggested he was zeroing in.

A bad pitch or a bad decision, the score would be tied and Prince Fielder would be in the batter's box.

Romo pondered the next pitch.

Behind him, at second base, Marco Scutaro was rooting for the fastball. In the regular season he'd seen Romo throw a half-dozen, more, sliders in a row and finally get beaten by his own stubbornness. The counts would go long, the hitter would see too many sliders, bad things happened. The veteran had pulled Romo aside.

"There's going to be situations like that," he told him, "if you had thrown a fastball to that guy he'd have had no chance."

Over Romo's right shoulder, shortstop Brandon Crawford positioned himself for the fastball, the way he always did between pitches. Even knowing Romo, knowing he'd probably throw a slider, it was habit. Crawford would line up fastball, neutral and adjust to the sign he saw.

Romo, Scutaro and Crawford waited for catcher Posey's sign. Slider. Romo shook his head. They knew then the fastball was coming. Manager Bruce Bochy knew, too, the fastball was coming.

"I liked it," Crawford said.

"Nobody," Scutaro said, "was expecting fastball right there."

[Also: Tampa Bay Rays to have a pair of odd giveaways this year]

Push play, and Miguel Cabrera, who, according to BaseballAnalytics.org, hit .379 against fastballs in the strike zone last season, lifted and dropped his left heel four times as Romo went into his windup. Posey shifted away from Cabrera to the outside corner, then another few inches farther, away from Cabrera and his lethal bat barrel.

"It was more of a gut feeling than anything," Romo said. "I think he was more set up for it. I think I probably could have thrown it the pitch before and gotten the same result. … I'm known for my breaking ball. And I'd already given him five of my best. You know, it just was time."

Romo found Posey's mitt and threw a four-seamer as hard as he could.

A good idea, Bochy thought.

"I didn't know he was going to throw it down the middle, obviously," he said, grinning. "If I did, I would have called time out."

Push play, the fastball started away, how Romo and Posey designed it. Cabrera lifted his left knee and drew back his bat. He leaned away, guessing slider, then hoping slider, and then the fastball tailed. It struck Posey's mitt at the level of Cabrera's thighs, a perfect, no-doubt strike with the perfect pitch. Cabrera turned from the plate.

"He called it a strike," Romo recalled, "before the umpire did."

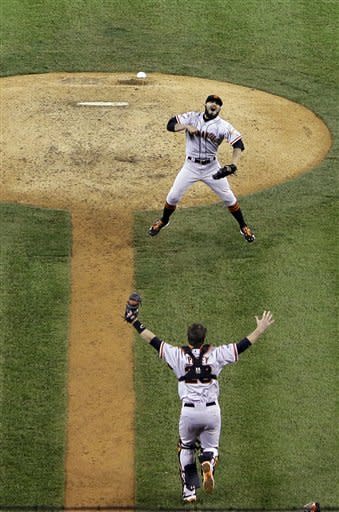

Push play, and Romo danced, and Posey leapt, and the infield filled with Giants. The slightest among them was Romo, who'd finished three World Series games. In a moment it had all become attainable, Romo was the last standing, the last cheering, the last crying.

Once, they'd handed him the baseball and the ninth inning and Romo didn't know if he could live up to it. He didn't know if he was good enough, or tough enough. But neither would he give the baseball or the ninth inning back. This would be his time, no matter the result. He'd figure it out. He'd be good and he'd be tough and he'd be no punk. In the minutes following the final strike, Posey smiled and told Romo he'd thrown "a ballsy pitch." Romo answered, "I really wasn't trying to be ballsy. I was trying to be smart."

He saw the replay dozens of times. Hundreds maybe. There was no missing the last out. The Giants win again, the littlest among them in there somewhere. He'd helped. He'd even been important. He could tell in their faces, by the way his teammates looked at him.

"It's the only time I feel big," Romo said. "It's the only time I feel visible. It's the only time I know my self-worth. No one questions that guy. This jersey means a lot to me. It's given me an opportunity to be somebody."

Push play.

"Who's that, mijo?"

"That's you, dad."

It really is.

More news from the Yahoo! Sports Minute:

Other popular content on Yahoo! Sports:

• Tim Tebow causes controversy with choice for speaking engagement

• Serious questions dog Dallas Cowboys

• Dominant Renan Barao further cements MMA standing

• Ranking the best of NBA's dunk contest