Searching for truth in a land where it's fleeting

On the day he found out they were going to make a movie about him, the first person Miguel Angel Sano told was his mom. "I'm gonna be famous," he said.

He spoke with the wonderment of an impoverished 15-year-old, which the world believed he was at the time. It is not that simple, of course, in the Dominican Republic. Something so fundamental as age is often a matter of dispute. The truth is pliable in the D.R. It bends and bows, molds itself to personal convenience, buoys those willing to exploit it. It is not supposed to do such things. The truth is supposed to be the truth, reality, a rock for the innocent, but then this is the Dominican Republic, where fact takes on multiple incarnations.

One truth, in Miguel Sano's case, emanates from the mouth of a man named Rene Gayo. He sits in an old Victorian chair. He is fat and mustachioed. His parents emigrated from Cuba to the United States, where he grew up and pursued a career in baseball – a career, by many accounts, filled with success. He has survived for more than a decade signing Latin American teenagers in hopes they grow into major league baseball players, first with the Cleveland Indians and today with the Pittsburgh Pirates. And he wants badly to sign another, who happens to be sitting in the room.

Gayo is in San Pedro de Macorís, a baseball hotbed and home of Sano, the most talented player to come out of the Dominican Republic in years. It is August 2009, more than a month after July 2, the magical day that Major League Baseball pours tens of millions of dollars into the Dominican economy. The truth is Sano is a star no matter how old he is, the sort of talent after whom teams lust. The truth isn't enough. Nobody wants to sign Sano after MLB spent months probing his age and identity. He has undergone DNA tests and bone scans, shown his hospital and school records, consented to the league's every request to verify he is indeed now 16 years old and his real name is Miguel Angel Sano.

Sano's parents believe Gayo knows why such questions emerged in the first place, and they have asked him to their house to explain. Their truth is rooted as much in speculation as anything. They believe Gayo has manufactured rumors that Sano is older than he claims to scare off other teams and drive his signing bonus demands down from the $6 million many expected him to receive. The Pirates are the only team still offering Sano a contract. They want to sign him for $2 million.

And Gayo says Melania Sano, her husband, Elvin Francisco, and all nine of the other people living in their home have every right to be mad. He trusts that Miguel is who he says he is and how old he says he is, that it shouldn't be this way, a teenager paying for the sins of peers and elders alike.

"Unfortunately," Rene Gayo says, "this is the country of lies."

On he goes, simultaneously charming and combative, playing the ally and the businessman, completely unaware of the one unimpeachable truth on that summer evening.

A hidden camera is capturing every word he speaks.

Let's try again: The truth doesn't exist here. The Dominican Republic is a web and wasteland of hustlers and pimps, moneymakers and moneytakers. It is a place where age and identity are transient, where pre-teens get shot with steroids, where the privileged have preyed on the poor, where an alleged child molester trained teenage boys for more than 20 years, where a baseball subculture has grown out of a shadow economy and into a cash crop.

MLB made a Faustian bargain with the Dominican Republic that it can neither clean up nor break, the fraud too deeply rooted in the system and the player pipeline too important to its daily operations. And because it happens in a place of immense poverty, where little English is spoken and less attention paid, baseball skates by with the overwhelming majority of its fan base unaware that the foreign country producing the largest number of major league players does so with a factory-farm mentality, its waste and runoff polluting all that surrounds it.

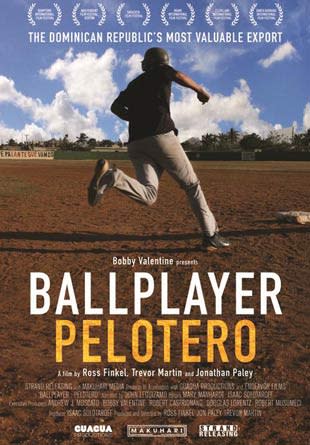

A new documentary, "Ballplayer: Pelotero," does its best to elucidate the dichotomy of the D.R. It follows Sano and another teenage prospect, Jean Carlos Batista, as they approach the Dominican Christmas, July 2. The movie provides an incisive look at the machine that churns out talent and the consequences it wreaks on the players, their families and baseball writ large.

Sano dropped out of school at 12 to enroll in the Dominican baseball machine full-time. The trainers, known as buscones, seek the most talented kids on the island and house them, feed them and clothe them in exchange for 25 to 35 percent of their signing bonus when they turn 16, MLB's minimum age for foreign players. Teams signed almost 400 Dominican players last year. They spent upward of $90 million on international players, the majority of that going to Dominicans.

It's not just the exorbitant money that urges players and trainers to resort to any and all means. Even meager bonuses of $10,000 represent a windfall to the 42.2 percent of Dominicans who, according to U.S. government statistics, live below the poverty line.

"I do believe there are some issues that are inherent to the country and to its culture – the poverty – that are going to make it difficult for baseball ever to be completely confident the signing of players is totally above board and consistent with what we would expect to be good standards of conducting business," said Mets general manager Sandy Alderson, who previously spent a year working for MLB trying to overhaul its Dominican operations. "At the same time, MLB cannot just sit idly and allow these things to happen. If nothing else, it can hold these clubs accountable for the things that happen there and do as much as it can to police the market."

One of baseball's problems is retrograde hypocrisy. For decades, MLB treated the Dominican Republic, an island of about 10 million, as its plantation. The league preferred players use buscones – often poorly educated themselves – to negotiate contracts instead of player agents. While the current generation of stars fetched healthy bonuses, the parasitic relationship limited David Ortiz's signing bonus to $10,000. Pedro Martinez got $6,500, Sammy Sosa $3,500, Miguel Tejada $2,000.

All of the usual trappings of money accompanied its injection into the Dominican baseball world: deceit, greed, ugliness. As one teenager in "Pelotero," which means ballplayer in Spanish, admits: "A lot of us have pulled off tricks so we can sign. People change their ages and all that. But that's what you have to do."

[Tim Brown: Searching for the heart of baseball in the Dominican Republic]

It's what some have to do. Not Sano. The movie introduces him early with healthy cracks of the bat. He looks different than the other teenagers: wiry strong, with a tapered torso and big butt, which scouts love. Sano comes across as funny, charming, sweet. He's called Bocaton, big mouth, a teenage kid who loves baseball and doesn't lament his lot in life, which is bad even for the D.R. At the beginning of the movie, Sano returns from the playing field to a shack, graffiti marking the outside, squalor the inside.

"It wasn't that it was small," said Rob Plummer, his agent. "The mattresses were rotted out. It was probably rat-infested. It was one of the worst situations I've seen."

So Plummer did what anyone invested heavily in Sano would do: He moved him and his family to a new house, the one where they sat down with Rene Gayo and tried to figure out what exactly he knew.

This is Rob Plummer's truth, as he says in the movie: "I basically broker Dominican 16-year-olds to Major League Baseball teams."

The line between sleazy and enterprising in the Dominican Republic is blurry, and Plummer has toed it for longer than any American agent with as much integrity as the system allows. On one hand, Plummer is quick to disassociate himself with players who fake their identity, either by changing their name or their birth date. On the other, he is admittedly single-minded when it comes to his job.

"I want to get the biggest signing bonus possible," he said. "I want to be like Scott Boras of the Dominican Republic."

When he graduated from law school at the University of Virginia, Plummer, now 43, noticed the vacuum for respectable player representation among Latin American teenagers. For three years, he worked hauling baggage to airplanes so he could fly on USAir for free. Philadelphia to San Juan, San Juan to Santo Domingo. In 1997, he took 26 trips, plenty of which focused on a kid named Ricardo Aramboles.

The Florida Marlins had signed Aramboles, a pitcher, for $5,500. He was 14. MLB invalidated the deal and declared Aramboles a free agent, free to sign when he turned 16. Plummer swooped in, negotiated a $1.52 million bonus with the Yankees and charged his standard 5 percent. Next came a record bonus for Joel Guzman, and suddenly one of the most powerful people in the Dominican Republic was a Jewish kid raised by a single mom in Philadelphia.

While Plummer's success turned against him – more established American agents' interests piqued once bonuses started hitting seven figures – his reputation and gravitas still mattered. When Plummer listed his million-dollar bonus babies, the peloteros perked up, and when he offered his services, they at least listened.

"The first time I saw Miguel," Plummer said, "I wanted to sign him."

Sano played hard to get. For six weeks, Plummer talked with him every day. He saw the immense power, even though Sano was dropping his hands and looping his swing. When Plummer pointed it out to Sano's buscon, Moreno Tejeda, the trainer got defensive. Who was this agent, this gringo, telling him how to do his job? Tejeda thought better of it. This was a partnership. Everyone involved needed to rear Sano with painstaking detail. They fixed the hitch. His game blossomed. Scouts flocked to see the 6-foot-3, 195-pound shortstop who could hit the ball a mile.

"Everybody who saw him thought he would be a huge impact player," said Gordon Blakeley, a top scout for the New York Yankees. "We saw him at a young age, and we just knew. We thought he was legitimately the person he said he was."

Such questions arise with every top prospect in the D.R. Is that really his name? His age? Sano's mom had a miscarriage at 17 years old, and that was enough to prompt MLB's investigation into whether he was misrepresenting his age and whether Melania was even his birth mother. A bone scan placed Sano's age between 16 and 18. A DNA test proved with 99.348 percent likelihood she was his mom. "Pelotero" captures her frustration boiling over. "This investigation is some bull(expletive)," she says as it lingers on for months.

[Tim Brown: Talent showcase was latest attempt to clean up Dominican scouting]

It's not uncommon for inquiries to stretch that long as MLB's Dominican-operations staff and Department of Investigations sort through myriad paperwork, medical tests and other methods of determining an identity. More than 10 percent of Dominican players who signed last year waited 100 days or more for contract approval, according to Baseball America. That didn't lessen Sano's concerns as July 2 approached. Teams spend a vast majority of their international bonuses on signing day – most through pre-arranged deals to which MLB turns a blind eye – and Sano knew without the investigation complete, his market was cratering.

On July 1, 2009, Sano and his family meet with Porfirio Veras, the commissioner of Dominican baseball, to plead their case. The scene in "Pelotero" captures Sano at the mercy of a system stealing millions of dollars from him.

"People take advantage of poverty here," Veras says. "I am totally clear. This is happening because he's poor."

The next day, Sano lounges shirtless in a plastic chair outside with family and friends. He scans the sports section of the newspaper. "DOS NUEVOS MILLONAIRO$," the headline reads – Two New Millionaires. The first is outfielder Wagner Mateo, who the St. Louis Cardinals sign for $3.1 million, a bonus they later would void because of Mateo's poor eyesight. The second is catcher Gary Sanchez, given $3 million by the Yankees.

Sano waits for his phone to ring with good news. It never does.

Of the 30 men in charge of teams' Latin American operations, Rene Gayo might be the most bombastic. He cuts a personality as large as his figure. Everyone knows him, and if you don't, you probably don't know much. Gayo brags he has signed 500 or 600 players, and though his job tends to breed such volume, it's nevertheless a significant barometer of the stroke he possesses. He makes and breaks careers, lives.

"If you look at it without emotions, yeah, I've got a lot of power in my hand everywhere I walk here," Gayo told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 2008. "But I look at that as something to be very careful with. As soon as that creeps into your mind, you'll lose sight of what we're really doing here."

The story told of Gayo's rise from failed minor-league catcher to part-time scout to power broker. Gayo said he understood the privilege, and he often repeated an axiom about his ability to change people's futures.

"I'm not God."

In his February 2011 plea deal with the U.S. government, David Wilder admitted that he and two subordinates with the Chicago White Sox engaged in a widespread scheme to skim bonus money from Latin American teenagers. Two scouts, Jorge Oquendo and Victor Mateo, would identify players for the White Sox to sign. They would tell Wilder, the team's director of player personnel, the player's skill level, his recommended bonus amount and how much of a kickback they would receive upon the player signing.

Between 2005 and 2008, Wilder received at least $402,000 for 23 players, according to the agreement. His scheme might've continued unchecked had a customs official not searched Wilder's baggage on a return trip from the D.R. to the United States and found nearly $40,000 in cash. After Wilder's guilty plea to one count of mail fraud, the judge recommended between 41 and 51 months in prison. Wilder awaits sentencing in September.

The depth of corruption in the Dominican Republic reaches far deeper than the age-and-identity issues that dogged Miguel Sano. MLB's transfer of such inquiries to its Department of Investigations in 2009, as well as a new registration system for top players, has stemmed the number of fresh bombshells dropped on teams when they realize they've been duped.

[Big League Stew: Eight first impressions on 2012 All-Star teams]

Former Washington Nationals GM Jim Bowden resigned after skimming allegations surfaced following the signing of 16-year-old Esmailyn Gonzalez for $1.4 million. Gonzalez was actually Carlos Lugo, a 20-year-old. The San Diego Padres were victimized three times between August 2008 and July 2009, the final time by an outfielder named Yeison Asencio, who took the name Yoan Alcantara, lived with a woman pretending to be his mother for two years and used a trainer to funnel a $25,000 bribe to an MLB investigator who cleared him even though he was three years older than he claimed.

Cases continue to leak in today. Baseball America last week reported George Soto, the son of longtime buscon Enrique Soto, was 21, not 17, when he signed with Seattle in 2007. Enrique Soto, who trained Miguel Tejada and scores of other major leaguers, was alleged by a report in the Dominican Republic to have sexually assaulted at least three of his former players. Yunior Peguero, one of the alleged victims, was murdered two weeks before July 4, 2011, when the television program Noticias Sin ran its report.

Among the widespread issues runs a common theme: neglect. Of children's welfare, of teams' money, of moral and ethical duties. The worst buscones shoot their players full of steroids to make their bodies look as fit as possible to scouts who might take a flier on a player based alone on how he looks. Dealing with 16-year-olds – the age at which almost all top Latin American players sign since teams want to shape them from the youngest age allowed – is an inexact science, and clubs mitigate risk by bringing in volume. Even in the Dominican Republic, the supply often cannot meet the demand.

The lack of oversight permeates the system. One GM described MLB's tack in the Dominican Republic thusly: "We give the scouts millions of dollars and tell them to sign some players. Club officials for the most part don't go down there. That's almost always true of GMs, presidents. CFOs who would go down there to audit big expenditures don't bother. Legal counsel don't know who to hire. It's out of sight, out of mind.

"But that's where the players are."

More than 11 percent of major leaguers on opening day rosters were born in the Dominican Republic, an offshoot of the academies teams built across the island to cultivate talent. Clubs realized any players they help rear in the United States are subject to the amateur draft in June. Relationships don't matter. Support for youth baseball in the United States becomes a community-relations line item on teams' budgets. Anything in Latin America is considered baseball-operations money.

Part of baseball's plan to clean up the D.R. is by unifying talent acquisition through a worldwide draft. Dominican baseball officials almost universally oppose their inclusion in a draft, fearful not only that it will restrict the cash flow coming into the country each July but choke off the economy that employs thousands across the country. Puerto Rico, once a robust baseball nation, has seen its talent pool wither since baseball included it in the draft in 1990.

The worldwide draft has support from MLB and the MLB Players Association and could turn into a reality by 2014 if baseball can rally the support of the D.R., Venezuela and other Latin American countries. Already MLB has irked officials with its invasive testing. They choose not to complain. Big business and big dollars always leave some collateral damage.

For now, the dollars aren't as big. MLB's new collective-bargaining agreement limits teams' expenditures in Latin America to $2.9 million between July 2, 2012 and July 1, 2013. A cynic might take it as baseball's rejoinder to the corruption. Don't want to clean up? Adios, bonus money.

Still, Dominican players and trainers aren't allowing MLB's crackdown to cramp their efforts to game the system. Baseball America recently reported that to combat DNA testing, some entire families are swapping identities. New names, new ages, new lives, clean DNA. Hustlers now and forever.

"Rene thinks he's going to get away with this," Melania Sano says. She's livid. Her son wants to play baseball. She wants him to start his career. And she is convinced Rene Gayo is the one impeding Miguel.

Melania's truth is whatever she feels. Never in "Pelotero" is actual evidence shown to convict Gayo of any wrongdoing. He vacillates between huckster and rainmaker. When Sano asks MLB for a meeting, Gayo shows up. The league is not going to clear him, Gayo says. Without his help, it's going to be difficult to sign.

"I'd really like to go inside and not be on film," he says.

Two hours later, they emerge from an office building. Sano says Gayo wanted him to say he was 19, "even though I'm only 16," and that the officials told him "they could end the investigation right away if we signed with the Pirates."

On July 24, MLB's investigation ends. The league partially clears Sano. He is who he says he is. The league refuses to say he is 16. There is not enough evidence to verify or disprove it. MLB's message: Sign Miguel Sano at your own risk.

No offers come in. Still just the Pirates. Melania snaps. She wants to lure Gayo into her new home and catch him explaining this on tape, hopeful he'll somehow implicate himself.

"It was an impulsive let's-film-him," said Ross Finkel, one of three co-directors of "Pelotero." "We were there. They asked us. We contacted some counsel to understand what the legal ramifications were. When we confirmed it was legal in that it was a private residence and the owner, we helped them film it."

She directs him to the Victorian chair and says it's the most comfortable. It's actually directly in the eye of the camera, which is hidden above.

Gayo sympathizes with Sano: "Even though you are telling the truth, you have to pay for that."

He claims Sano's clearing came because of him: "What I did is get him amnesty. I have influence. It's not a problem. All you have to do is cooperate."

The video cuts off. The audio continues to roll.

"You don't have any problems because you've got me."

The film makes it clear, through the comments of Sano's family and its own editing, that Rene Gayo is the villain of this case. The Pirates issued a statement to Yahoo! Sports on Sunday afternoon that included a defense of Gayo, who continues to run their Latin American operations.

“Rene Gayo has been helping young players from Latin America fulfill their dreams for nearly twenty years. Rene has earned the respect and trust of countless young players and their buscons (sic) because of how transparently he conducts the recruitment, evaluation and signing process."

Two phone calls placed to Gayo on Sunday went to voicemail. He replied via text message and referred any questions about "Pelotero" to a Pirates media-relations official.

He sent a follow-up text.

"There is no defense for the truth."

Miguel Sano is listed on the Beloit Snappers roster as 19 years old. He is 235 pounds now and has moved to third base. According to one scout watching him at a Class-A Midwest League game in Burlington, Iowa, he is the best power-hitting prospect in baseball. His batting practice is a flurry of balls that seem impervious to gravity. His in-game power is just as righteous.

"That's our hidden gun," said Ron Gardenhire, manager of the Minnesota Twins, who signed Sano for $3.15 million on Sept. 29, 2009. They had lurked in the background from the start, along with the Yankees and Baltimore Orioles. While the investigation soured most teams, the Twins kept in touch with Plummer and offered Sano the biggest bonus in team history. Sano did not give the Pirates a chance to match or exceed.

In spring training this year, the Twins parked Sano in minor-league camp, far from the eyes of most scouts. "They don't want to show him off too much," Gardenhire said. "We get excited in the big leagues when we see a swing like that."

For now, Sano treads the path of almost every minor-league player: step by step, rung by rung, climb and claw toward the major leagues. His 17 home runs lead the league. His 95 strikeouts rank second. He walks at a surprisingly high clip. It would be fair to call his defense at third base bad. As with every teenager, good comes with bad, triumphs with stumbles.

A few weeks ago, Twins GM Terry Ryan visited Sano and issued an edict for him and Beloit manager Nelson Prada: "No more weight." He doesn't want Sano eating himself off third base. So at a Mongolian barbecue restaurant inside the Pzazz casino, where the Snappers stay while in Burlington, Sano opts for shrimp and vegetables, with a few carbs thrown in for energy.

The extra 40 pounds make him even more imposing, like a teenage Hanley Ramirez. Sano wears a DKNY shirt and checkerboard shorts. While Sano has an undeniable presence – he earned the nickname Bocaton from Plummer and lives up to it in the clubhouse, even if his English is a work-in-progress – he is not wont to flaunt it. You know he is Miguel Sano; you just don't learn it from a gold chain.

"Pelotero" comes out in theaters in New York, Los Angeles and Minneapolis, plus on demand and on iTunes, on July 13. The movie will not make Sano a star. His bat will do that. It will give people a far better insight into how the Dominican sausage is made, however, and it's a story rife with discomfort and opportunism.

"Everything the movie says is true," Sano said. "That's how it happened. They took me to New York to watch it on a big screen. I was surprised. Everything was the same. Everything we went through."

Prada, Sano's manager, translates his words. After signing with the Twins for $7,000 out of Venezuela, he played four years, then started coaching before spending the last eight seasons as a manager. Never in a career that's coming up on two decades, Prada said, has he come across a player as young and talented as Sano.

"In this world, people do what they need to do to find good players," Prada said. "There's a competition among 30 teams. We see a lot of dirty stuff in our countries."

Sano nods along. He is on his second plate of shrimp. He is happy. The Twins treat him well. He got paid, albeit half of what he may have gotten otherwise. His approach is far more mature than a typical 19-year-old.

"I don't have any bad feelings for anybody," Sano said. "The way I grew up, my family taught me I don't want to have any ill will. Whatever happened at the moment happened. I'm doing what I want. There's no reason to be angry.

"You know, I call him sometimes to say, 'How you do?' "

Call who?

"Gayo," Sano said. "I think the guy is a normal guy. He's not a bad guy. Maybe the Pirates said to him, 'Hey, do this,' and he had to."

In the opening scene of "Pelotero," goats run across dirt fields in San Pedro de Macorís as children play catch and whack balls and play as one might imagine children in the Dominican Republic play. The scene cuts to a buscon named Astin Jacobo Jr.

"When you deal in baseball, young kids, it's like when you go and harvest the land," he says. "You put the seed in the land, and then you put water in it, you clear it. You do all of this and when it grows – you sell it. It's just the way it is."

Never mind the allusions to the D.R. being baseball's plantation. Jacobo tells the only truth of baseball in the Dominican Republic: It is no longer a third-world oasis from which stories of great triumph emerge. It is dirty. It is filthy. It trades in blood money. Even Jacobo, seemingly one of the legitimate and caring buscones, cannot evade the corruption perpetuated by Batista, the other player, and his mother, a story that runs parallel and opposite of Sano's.

In the end, Miguel Sano wins. Maybe Rene Gayo did launch the investigation. Maybe he didn't. Maybe Miguel Sano was 16. Maybe he wasn't. We don't know. We may never. As Moreno Tejeda, Sano's trainer, says: "From here on out his real age will always remain in doubt."

Any questions about it paused when Sano received his passport. He is free to travel between the D.R. and the United States, between his newest house, with a pool and chandelier, and his adopted home, where he's going to make millions more. The filmmakers have followed him around Beloit this season. Gone to his house, seen his workouts, parked in the dugouts, sat in on meetings. They think a film about the climb from the slums of San Pedro to the bright lights of the big leagues will make a worthwhile sequel.

An epilogue constitutes the final frames of "Pelotero." The directors relay their attempts to film Rene Gayo's rebuttal. He declines. Instead, Gayo issues a statement:

"Everyone involved was guilty of doing what their job descriptions demand and unfortunately this created confusion for the Sano family."

His job demands he sign the best players possible for the Pirates organization, and that's what he was doing. Just as Miguel Sano was trying to score the biggest contract ever in Latin America, and somebody with an agenda got in his way. Just as every buscon who proffers steroids and every kid who changes his age and every scout who skims is doing what he must to win in the Dominican Republic, where the truth only gets in the way.

Other popular content on Yahoo! Sports:

• Dan Wetzel: Joe Paterno's role in Jerry Sandusky cover-up grows as evidence is leaked

• Usain Bolt blames twitch from competitor on starting blocks for second-place finish

• Tim Brown: Mets knuckleballer R.A. Dickey continues to amaze