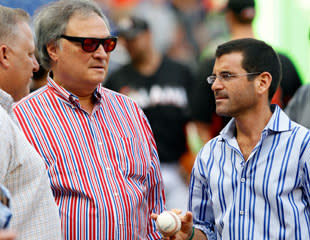

Marlins' Jeffrey Loria and David Samson conned Miami, lined their pockets and held a fire sale

Here is how the con worked.

The Florida Marlins owners whined, and they brayed, and they swore up and down that they couldn't afford the new stadium necessary to raise their payroll from embarrassing levels and compete annually. And they got it, the vast majority on the taxpayer's teat no less, this gleaming new gem from which they would fatten their pockets by taking all of the ticket and concession and parking and advertising sales, every last cent, no matter how unseemly that felt.

To allay fears, they changed their name to the Miami Marlins, their colors to a rainbow vomiting, their image to reflect the city, hot enough that the New Yorker would profile them and Showtime would broadcast a documentary on them and free agents Jose Reyes and Mark Buehrle and Heath Bell would take the money. People actually bought into the thing, recognized them as a real team and not just some affiliate run by a couple of swindlers who had already screwed Montreal and were primed to do the same to another city.

It wasn't ever going to end any other way. You knew that. You knew. When Jeffrey Loria and David Samson are involved, it can't end any other way, because they know no different. Loria is the owner of the Marlins, Samson the president, and they're turning the Miami Marlins into a chop shop. Anibal Sanchez and Omar Infante were traded first this week, to the Tigers. Then Hanley Ramirez, who until this year Loria regarded as the franchise, to the Dodgers. Next could be Josh Johnson, their homegrown ace.

[More Jeff Passan: Hanley Ramirez is a worthy Dodgers gamble if his issues evaporate]

That would be $32.75 million shed within a week, bringing the Marlins from their $100 million dream back to the bottom quarter of payrolls in baseball.

And Miami is stuck with $2.4 billion in stadium debt service for that.

This would be falling-down funny if it weren't so very sad. Two charlatans, ripping off a major American city and laughing all the way to the bank.

"We're going to play our significant games in August and September, and by that time people will be so in love with us they won't want to go anywhere else!" – Jeffrey Loria, to the Miami Herald, on June 29.

Here is how they perpetuate the con.

It's little things. Telling people this team will be relevant toward the end of the season and setting it aflame in July. Spending years talking about how the season-ticket base was 5,000 when it was only 2,000. Lies. Small lies that build up into a mountain of distrust, anger and resentment.

Like Samson's assertion to reporters that one of the reasons for their disappointing attendance at Marlins Park was because of the Miami Heat's playoff run. It's a classic Samson trick: Say something that sounds like it makes sense, let the public believe it and skate by with an excuse that's better explained by, you know, the fact that fans may well be nauseated by owners whose idea of a great ballpark attraction is a $3 million acid trip of a home-run feature in center field.

The Heat's first playoff game was April 28. They won the NBA championship June 21. For every home game between those dates, the Marlins averaged a crowd of 28,194. When the Marlins and Heat played at home on the same day, that number dropped less than 2 percent, to 27,729.

What have the Marlins drawn at home on the dates outside of the NBA playoffs? Exactly 28,774 per game, and if you want a more realistic idea of an average game, take away opening day – the only sellout the Marlins have been able to muster in their supposed must-see ballpark – and the number dips to 28,402. In other words, the difference between a regular Marlins game and one on a day in which the Heat hosted a playoff game was 208 fans after opening day, 673 fans including that game.

And considering tickets for the next three Marlins home games are going for $2.50, $2.50 and $2 apiece, it's not like those 673 people had a great reason to stay away. It's a testament, actually, to the people of Miami, who are either so sickened by the Marlins or ambivalent toward them that neither a campaign of glitz nor an offseason of spin could lure them into this den of blood money.

[MLB Full Count: Watch live look-ins and highlights for free all season long]

The announced attendance Tuesday night was 25,616, though the place looked about half of its 37,000-seat capacity, if that. For the architectural wonderment surrounding Marlins Park, fans – the people whose tax dollars not only raised the thing but will funnel more cash into Loria and Samson's coffers – seem rather disinclined to go. On May 30, against the first-place Washington Nationals, in the final game of the Marlins' best month in team history, the announced attendance was 24,224.

While a wonderful metaphor for the 2012 Marlins would be the patches of brown grass that have pervaded the field most of the summer, we need not use any literary device to encapsulate what a disaster it's been. Just fact. And that fact is that David Samson was so aggrieved that the Marlins wouldn't have representation at the All-Star game after Giancarlo Stanton's injury, he took it upon himself to suggest a replacement: outfielder Justin Ruggiano.

Who still has more at-bats in Triple-A than he does in the major leagues this season.

"We're not nearly out of it – the second wild card or even the division." – David Samson, to the Sun-Sentinel, on July 8.

Here is how the con evolves, like a disease adapting to fight off what's trying to kill it.

On the same day Samson uttered those words, he reiterated the same pabulum that Loria had for years: That Hanley Ramirez, notorious loafer, wretched teammate – the guy who has missed time recently because he didn't take the antibiotics to stem an infection on his hand that festered after he punched a cooling fan – "is the man on this team."

The Marlins had coddled Ramirez ever since savvy general manager Larry Beinfest acquired him and Sanchez in the Josh Beckett deal with Boston before the 2006 season. His antics flew because Loria, wonderful judge of character he is, liked him. Now Loria must figure out how to salvage his precious Baseball in Motion art installation, Ramirez's memory sullying the last panel.

This is baseball in Miami: an art project, full of sharp angles and muddled imagery, the vision of two men who are clueless as to what baseball fans really want. Not art, not beauty, not anything so ethereal. Just baseball. Winning baseball.

The sort that doesn't come from spending sprees alone. The idea that a Marlins team that went 72-90 last year suddenly would contend with the addition of a shortstop, a starter and a reliever seems, in hindsight, rather far-fetched. Maybe the growth of Stanton and Logan Morrison, the return of Johnson and the guidance of new manager Ozzie Guillen would coalesce into something majestic.

It hasn't, and the Marlins, so used to going all Kevorkian on their seasons, dumped Ramirez and his excessive contract, and Sanchez before he left via free agency. Taken on their face, those two moves are defensible.

Even entertaining offers for Johnson now – and sources say the Marlins are not just doing that but expect the team to deal him – says the Marlins are looking past 2013, too, and that's where the ideal of this new team, this new era, comes crashing down.

Samson said from the start that the Marlins carrying a hefty payroll was contingent on fans showing up. There aren't nearly as many as the team hoped, and with ticket sales often cratering in Year 2 of a new ballpark, the Marlins might've actually – gasp! – threatened to take a loss had they not gone into sell mode.

Surely they'll cry poor either way, considering Samson might as well have claimed insolvency when the Marlins were raking in nearly $50 million in profits the two years before Miami-Dade County approved the funding for the stadium. It's how they do business.

The idea that the Marlins are going to re-allocate this money toward more players this offseason is laughable. They wouldn't be trading for young pitchers Jacob Turner and Nate Eovaldi, and dangling Johnson for prospects, unless they planned on going bargain basement around Reyes, Stanton and the rest of the core. It didn't take a cynic to think this iteration of the Marlins would have a short shelf life, but four months? Even the most jaded, yours truly, figured they would let it ride at least a year to reward those who actually bought in.

That, of course, is giving Jeffrey Loria and David Samson too much credit. They're awfully good businessmen, if you consider the ability to fleece feckless politicians and wring every last cent out of a metropolitan area a skill. What they lack in morals they make up for in social faux pas.

On June 21, the Marlins had lost six of seven games and fallen two games under .500. Loria decided it was an appropriate time to give the team a pep talk. One player there called it "possibly the worst speech I've ever heard." The Marlins lost that day and then four of their next five.

Loria didn't understand that it takes gravitas to give a speech like that, the sort owned by Nolan Ryan or George Steinbrenner or not Jeffrey Loria. Players, executive, fans – they don't see him like that, not even close. They see him for exactly what he is: the architect of the biggest con in sports.

Other popular content on Yahoo! Sports:

• Steve Henson: Matt Barkley's commitment to USC can give Penn State hope

• Pat Forde: Scandal is all around college athletics

• Adrian Wojnarowski: Carmelo Anthony’s flaws hidden among greatness of Team USA