DHS warns of Russian interference plans in 2020 elections, as Washington focuses on Ukraine

WASHINGTON — U.S. government efforts to prevent Russia from conducting influence operations directed at American audiences have largely failed, and Moscow is continuing its attempts to influence the American political system by exacerbating social divisions, with a particular focus on the upcoming 2020 presidential elections, according to an unclassified intelligence assessment obtained by Yahoo News.

“Russian influence actors almost certainly will continue to target U.S. audiences with influence activities that seek to advance Russian interests, and probably view the 2020 presidential election as a key opportunity to do so,” says a recent intelligence assessment from the Department of Homeland Security’s Cyber Mission Center.

The intelligence assessment, which cites DHS monitoring, classified reporting and open source information, says that Russia has continued through this year to “to engage in influence activities intended to cultivate relationships with U.S. social media users, despite consequences of sanctions, social media account take-downs, and diplomatic overtures…”

The DHS assessment, which was coordinated with the FBI, the CIA, the NSA and other intelligence agencies, comes at a time when fears about disinformation and foreign influence operations are politically charged. President Trump is currently embroiled in an impeachment inquiry examining his alleged efforts to pressure Ukraine to interfere in the U.S. election process, and his former Democratic opponent, Hillary Clinton recently claimed that Democratic primary candidate Tulsi Gabbard “is a favorite of the Russians,” asserting that that Russia “has a bunch of sites and bots and other ways of supporting her so far.”

Yet beyond the partisan battles, the recent DHS report, dated Sept. 12, 2019, and marked “for official use only,” shows that government officials behind the scenes are continuing to sound the alarm about the type of Russian electoral interference that took place in 2016. It’s an alarm, however, that experts say few in Washington seem to be heeding.

“The big problem in the U.S. is that there has been no high-level political attention to this,” says Alina Polyakova, founding director of the Project on Global Democracy and Emerging Technology at the Brookings Institution. “Congress has not passed one single legislative bill to at least try to curb the spread of disinformation online.”

But as Washington remains mired in partisan battles over disinformation and foreign influence, Russia appears to be moving forward with its own plans.

The report reveals that the DHS monitored “a small sample of 22 social media accounts suspected of being controlled by Russian influence actors on social media platforms from early September 2018 to early January 2019,” and found they “amplified divisive narratives, including content critical of US and allied foreign policy, racial discrimination and tensions, US politics and political figures, climate change, and environmentalism.”

Those Russian-controlled accounts also targeted specific U.S. communities, the report says.

“Russian influence actors’ efforts on social media continued through at least early January 2019,” says the report, “to focus on themes including aggravating social and racial tensions, undermining trust in US authorities, stoking political resentment in racial minority communities, and criticizing perceived anti-Russia politicians, based on DHS observation of these accounts’ activity.”

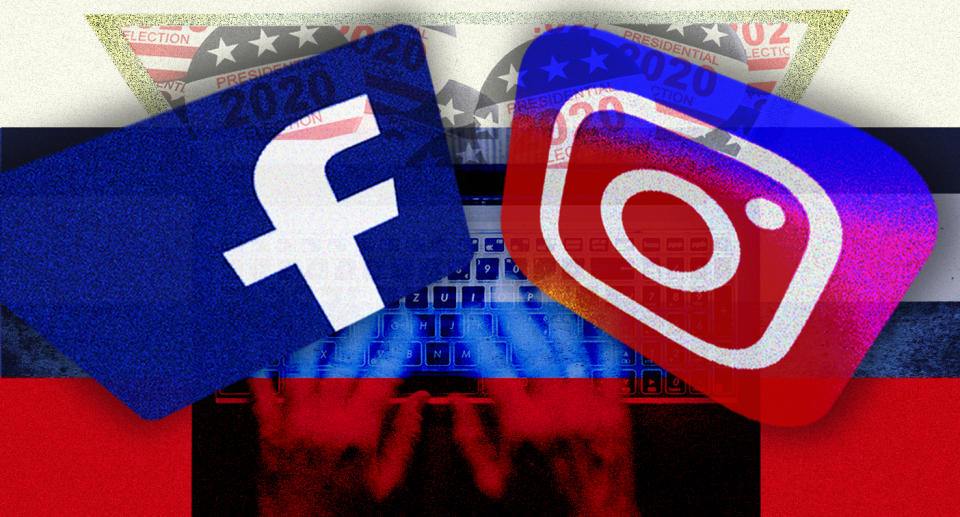

The DHS did not respond to a request for comment about the report, but the conclusions in its assessment appear to be backed up by recent public reports as well. Earlier this week, Facebook revealed that Instagram accounts originating in Russia are already active, with some posing as swing state residents. The company’s announcement just two weeks after the Senate Intelligence Committee released a report providing more details about how Russia targeted American voters with a disinformation campaign designed to help Donald Trump win the 2016 presidential election against Hillary Clinton using a combination of targeted advertising, fake news and content that exploited divisive social issues.

That interference, however, is morphing and posing new threats for the upcoming presidential election. In the 2016 elections, the Internet Research Agency, a St. Petersburg-based company, ran online “troll farms” that posted inflammatory political rhetoric, but its focus is now on “amplifying content rather than relying on fake accounts to create new content,” says the report.

That’s a strategy that outside researchers see as well.

“Eliminating the risk of building an audience by just commandeering an audience that’s already there is the absolute most rational thing for anyone running one of these campaigns to do,” says Renée DiResta, a 2019 Mozilla Fellow in Media, Misinformation, and Trust who has advised Congress and the State Department. “People on the internet tell you who they are; if you want to go and find people it takes all of five minutes to go to Facebook and identify the biggest or most active meme groups and just start putting your content in there.”

DiResta cited the example of a network of pro-police Blue Lives Matter pages that were uncovered by Stanford Internet Observatory researchers before being taken down by Facebook. The nine pages with 312,000 followers, which drew visitors by promoting pro-Trump, pro-police content, were produced out of Kosovo for financial gain.

Researchers observed that users in Kosovo were creating fake content, “and then they posted the content from the fake pages into real groups,” says DiResta. “And that is how they did the work of generating their audience.”

While the threat may not be entirely new the problem, says experts, is that the U.S. government has done little to stop this sort of disinformation since the 2016 election.

“Russia is doubling down on information operations, yes, they’re trying to sow discord and animosity, that’s their primary M.O.,” says Michael Carpenter, senior director of the Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement. “They’re running rampant.”

Yet there is no legal or regulatory framework in place to counter those operations, according to Carpenter.

“If a Russian NGO that is masked behind several layers of shell companies in the U.S., has an American sounding name, is contributing a couple thousand bucks to some alt-right website, it’s not even illegal,” he says, “nor is it traceable, nor does that website have any obligation to disclose its donors to the FEC or anyone else.”

Polyakova of Brookings agrees that some sort of regulation is required, because the private sector alone isn’t equipped to take on the problem. “Social media companies have been self-governing, but that self-governing has to come to an end because it’s not solving the problem,” she says.

One of the things that could be done, says Polyakova, is the creation of an agency for social media companies that “set things like standard terms of use and service,” similar to what takes place in the financial and banking sector for money laundering. “This independent regulator could do something like that,” she says.

In addition to a well-coordinated government response, a coherent narrative is also essential to the success of any counter-influence campaign, says Nina Jankowicz, a fellow at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C. “I think the effective responses that we've seen in Europe have been ones that name the problem explicitly and name the actors involved and put the whole force of the government behind solving it.”

Jankowicz points to the U.K.’s response to the attempted assassination of Russian double-agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter as a model for fighting back against Moscow’s disinformation. The U.K., in response to Moscow’s efforts, launched its own information campaign of its own, setting up, for instance, a communications team to publicly release information about Russian intelligence officers responsible for the attack.

In the U.S., on the other hand, says Jankowicz, a similar effort is limited by the politicization of debate around Russian disinformation. “In order for all these cogs to move together, someone needs to press the button,” says Jankowicz.

While the enforcement landscape today is much better today than it was before the 2016 elections, it remains limited in its capacity to disrupt influence campaigns, says Alex Stamos, former chief security officer at Facebook and now an adjunct professor at Stanford University.

“In the run-up to the 2018 midterms, DHS created their task force, the FBI created a foreign influence task force, NSA spun up a group whose job it was to watch and pay attention to foreign disinformation actors, not just transnational operational cyber actors, [and] that’s been great,” he says.

Still, Stamos says structural issues continue to hamper an effective response to the problem.

“The FBI and DHS are limited to even monitor for domestic misinformation and our foreign adversaries know that. The FBI can only investigate things if there’s a possible predicate of a law being broken,” he says. “There’s huge classes of things that foreign adversaries can do.”

Even with that progress, there are limits to what private companies and government agencies can do. “The companies know very little about what lies behind different entities. Facebook can’t serve or subpoena to find out how some super-PAC was funded. The FBI can do that but the FBI doesn’t have access to the content data, except when they have individualized suspicion,” he says. “The different groups who are watching all have very different views of the data but no one has access to all of it.”

On an even more basic level, says Elina Treyger, a political scientist at Rand Corp., the U.S. must decide what its objectives are in combating influence operations. “We talk about countering what the Russians are doing, but there is rarely a clear goal behind the countermeasures,” she says. “What is it that we want to accomplish?”

If the goal is trying to protect the public from foreign influence operations, then the U.S. is failing, she says.

Treyger contrasts the United States with Finland, which has incorporated courses on disinformation, fact checking and voter literacy into its educational system. Noting that such programs work better in countries with higher trust in institutions and a more uniformly educated population, Treyger says Americans remain vulnerable to disinformation.

“This is a problem that’s obviously bigger than Russia,” she says. “[It’s] one of the defining problems of our current political moment.”

_____

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News: