Orionid Meteor Shower Is Peaking Now: How to See It

If you step outside before dawn during the next week or so, you might be able to see bright meteors streaking through the sky.

The Orionid meteor shower is peaking now, and it will likely be a very good show this year, weather permitting. The moon will be slimmed down to a narrow crescent before sunrise on Tuesday (Oct. 21) morning during the peak of the shower. The skinny lunar sliver will not even rise until around 5 a.m. local time. Even if you can't see the meteor shower from outside your home, you can watch it live online. NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama will host a webcast tonight (Oct. 20) starting at 10 p.m. EDT (0200 Oct. 20 GMT) featuring live views of the meteor shower. You can watch the meteor shower webcast on Space.com.

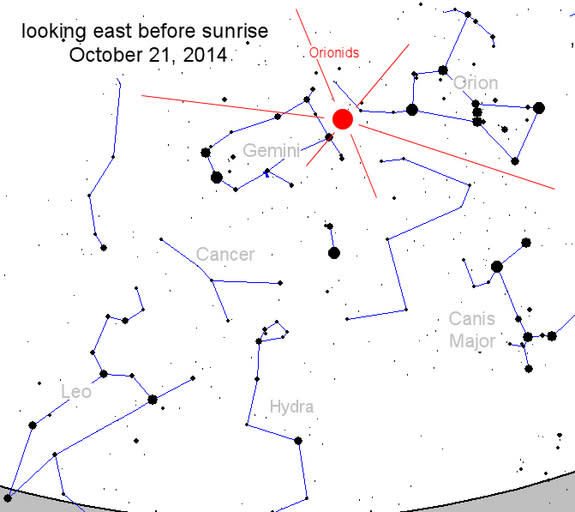

The Orionids can best be described as a junior version of the famous Perseid meteor shower. The meteors are known as "Orionids" because they seem to fan out from a region to the north of the constellation Orion’s second brightest star, Betelgeuse. [See amazing photos of the Orionid meteor shower of 2013]

Currently, Orion appears ahead of Earth in the planet's journey around the sun, and does not completely rise above the eastern horizon until after 11:00 p.m. local time.

The Orionid meteor shower appears to radiate out from the constellation Orion each October. The meteor shower is the result of debris from Halley's Comet striking Earth's atmosphere.

Credit: Dr. Tony Phillips/Science@NASA

Halley’s Legacy

The Orionid meteor shower is created each year when Earth passes through dust left behind by the famous Halley's Comet.

The comet actually creates two different meteor showers on Earth every year. The orbit of Halley’s Comet closely approaches the Earth’s orbit at two places. One point is in the early part of May, producing a meteor display known as the Eta Aquarids. The other point comes in the middle to latter part of October, producing the Orionids.

Comets are the leftovers from when the solar system first formed, the odd bits and pieces of simple gases – methane, ammonia, carbon dioxide and water vapor – that went unused when the sun and its attendant planets came into their present form.

These tiny particles – mostly ranging in size from dust to sand grains – remain along the original comet’s orbit, creating a “river of rubble” in space. In the case of Halley’s comet, which has likely circled the sun many hundreds, if not thousands of times, its dirty trail of debris has been distributed more or less uniformly all along its entire orbit. When these tiny bits of comet collide with Earth, friction with our atmosphere raises them to white heat and produces the effect popularly referred to as “shooting stars.”

What to Expect

The best time to watch the meteor shower begins from 1 or 2 a.m. local time until around dawn, when the constellation Orion is highest above the horizon. The higher in the sky Orion is, the more meteors appear all over the bowl of the sky. The Orionids are one of just a handful of known meteor showers that can be observed equally well from both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

Typically, Orionid meteors are normally dim and not well seen from urban locations, so it’s suggested that you find a safe rural location to see the best Orionid activity.

The Orionids are one of the better annual displays, producing about 15 to 20 meteors per hour at their peak. Add the 5 to 10 sporadic meteors that always are plunging into our atmosphere and you get a maximum of about 20 to 30 meteors per hour for a dark sky location. Most of these meteors are relatively faint, however, so any light pollution will cut the total way down.

The shower may be quite active for several days before or after its broad maximum, which may last from the 20th through the 24th. Step outside before sunrise on any of these mornings and if you catch sight of a meteor, there’s about a 75 percent chance that it likely originated from the nucleus of Halley’s Comet. After peaking on the morning of Oct. 21, activity will begin to slow, dropping back to around five per hour around Oct. 26. The last stragglers usually appear sometime in early to mid November.

"They are easily identified … from their speed," David Levy and Stephen Edberg write in "Observe: Meteors," an Astronomical League manual. "At 66 kilometers (41 miles) per second, they appear as fast streaks, faster by a hair than their sisters, the Eta Aquarids of May. And like the Eta Aquarids, the brightest of family tend to leave long-lasting trains. Fireballs are possible three days after maximum."

You can also watch another meteor shower webcast featuring expert commentary about the Orionids on Tuesday night via the Slooh Community Observatory.

Editor's Note: If you snap an amazing picture of the Orionid meteor shower or any other night sky view that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Copyright 2014 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.