Asteroid Hunter: An Interview with NEOSSat Scientist Alan Hildebrand

Update: Canada's asteroid hunting NEOSSat successfully launched from India on Monday, Feb. 25. For the latest news read: Indian Rocket Launches Asteroid-Hunting Satellite, Tiny Space Telescopes

A Canadian satellite poised to launch Monday (Feb. 25) is taking the search for asteroids near Earth into orbit.

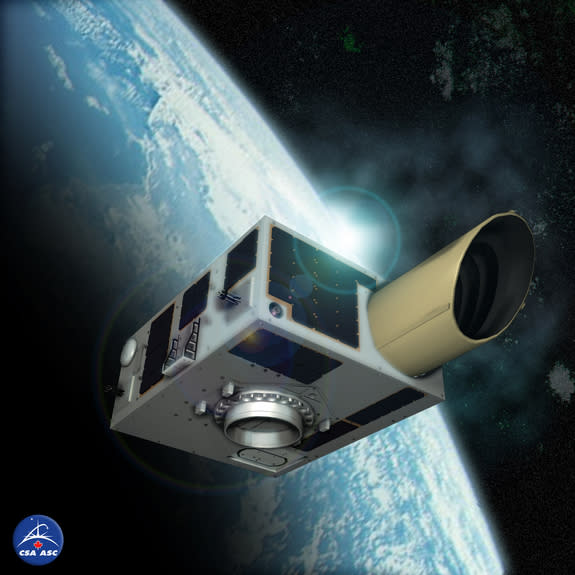

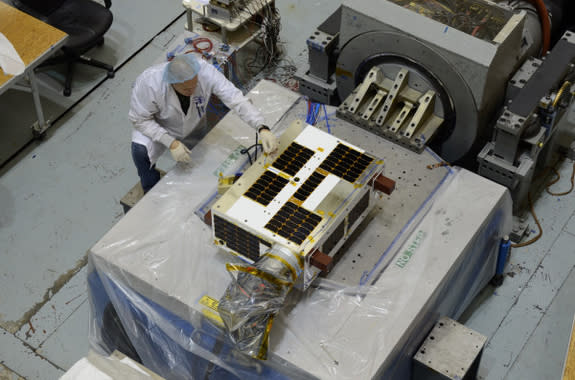

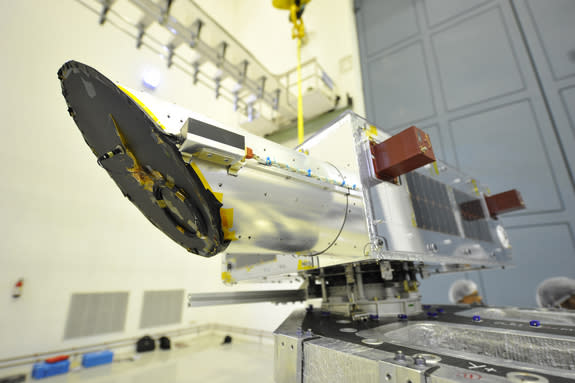

The suitcase-size Near Earth Object Surveillance Satellite (NEOSSat) will launch Monday (Feb. 25) atop an Indian Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle and seek out large asteroids from an orbit about 497 miles (800 kilometers) above Earth.

While asteroid 2012 DA14 buzzed by Earth at a distance of 17,200 miles (27,680 km) on Feb. 15, NEOSSat's focus will be on asteroids at least 31 million miles (50 million km) away from the planet. The satellite will also track the paths of space junk (leftover pieces of rockets and spacecraft) in orbit.

Canada's inspiration for seeking asteroids came after the country launched the suitcase-size Microvariability and Oscillations of Stars (MOST) space telescope in June 2003. Scientists built on MOST's architectural concepts as they proposed NEOSSat, according to NEOSSat co-principal investigator Alan Hildebrand.

SPACE.com spoke with Hildebrand, a planetary scientist with the University of Calgary, to get an close-up view of the asteroid mission:

What is the advantage of having a spacecraft searching asteroids, over a ground-based observatory?

Our project uses NEOSSat to search for asteroids. The telescope is small, only a 15-centimeter [5.9 inches] telescope. It can’t see particularly faint asteroids, and we can’t cover a lot of them, but what we can do — and the mission the spacecraft is designed for — is that we can efficiently search the sky, near the sun. That is tough for ground-based telescopes to do because of the day-night cycle. [See how NEOSSat tracks asteroids (Video)]

So searching the sky, close to the sun, we’re able to relatively efficiently find asteroids in orbit that are relatively close to the sun. Those are called the orbital classes Atira — those are the ones entirely inside Earth’s orbit and never cross it — and Aten class, which spend most of their time inside Earth’s orbit and once in a while do cross Earth’s orbit. So NEOSSat is good at finding those two classes of asteroid.

Why is Canada so interested in hunting asteroids?

The Canadian Space Agency had funded another mission called the MOST [Microvariability and Oscillations of Stars], which was a stellar photometer [telescope]. That was a different science objective, but the capability of that satellite when they built it, they and the contractor, made us wonder what could we do with this new technology. One application was doing asteroid searching. So we did a concept study for the CSA, and this survey of the region near the sun. What we came up with was a unique and useful science contribution.

What are your primary scientific goals for the mission?

We hope to most better understand the Atira class of asteroids. How big is it, what is the distribution, how many asteroids in the solar system. It would be very fun if were able to find an asteroid or two that were close to the Earth, dynamically, so that they were easy exploration targets for spacecraft or crude missions. One of the people on the science team did simulations of the [asteroid] population. We would have to be relatively lucky to find an asteroid particularly dynamically close to the Earth, but it’s certainly possible. [The 7 Strangest Asteroids in the Solar System]

You're saying it's possible these asteroid targets could be used in the future for mining exploration?

It's possible, yes.

What kind of targets, in particular, would these companies be looking for?

The economics all comes down to orbits. When orbits are different — either by their size or their inclination, or they are tipped — it takes a lot of energy to go from one to the other. That equals dollars and risk. It is much easier to get to somewhere that has an orbit in the same inclination as the Earth ... As you know, we send spacecraft to Mars all the time. We send spacecraft to Mars because it is in the same plane as the Earth.

Most of the asteroids are in different planes, so it takes a lot of energy to get there. It comes down to finding an asteroid that is close to us dynamically for easy exploration and easy exploitation. I’m not saying it would be easy — it would be hard — but it would be possible.

What is the typical size, distance and composition of the asteroids you're seeking?

We would typically be finding asteroids, let’s say, relatively distant from Earth. Fifty or 100 million kilometers [31 million to 62 million miles] away, and at that distance, they have to be relatively large for us to find them some hundreds of meters [or feet] in diameter or more. So that asteroid [2012 DA14], the one that is going to zoom by the Earth within the communications satellites' orbit, it’s relatively small. It's a 40-meter [131 feet] rock. We’ll be finding asteroids that are much bigger, because they’re farther away.

This telescope can see a light of a certain intensity, so if your object in that certain intensity is far away, it’s going to be bigger in general. We are not looking for asteroids close to the Earth. Naturally, if something is close, comes into our field of view we would detect it. But we’re targeting a certain patch of sky ... if you were looking at things zooming in at the Earth, we would instead scan the sky every couple of days. That is not how our survey is designed.

Editor's note:Canada's NEOSSat mission will launch at 7:20 a.m. EST (1220 GMT) on Monday from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre in Sriharikota, India. You can watch the launch of NEOSSat live via India's official Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle webcast.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Copyright 2013 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.